Big Game Hunting: The Evolution of INDRIK SPIDER From Dridex Wire Fraud to BitPaymer Targeted Ransomware

INDRIK SPIDER is a sophisticated eCrime group that has been operating Dridex since June 2014. In 2015 and 2016, Dridex was one of the most prolific eCrime banking trojans on the market and, since 2014, those efforts are thought to have netted INDRIK SPIDER millions of dollars in criminal profits. Throughout its years of operation, Dridex has received multiple updates with new modules developed and new anti-analysis features added to the malware.

In August 2017, a new ransomware variant identified as BitPaymer was reported to have ransomed the U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS), with a high ransom demand of 53 BTC (approximately $200,000 USD). The targeting of an organization rather than individuals, and the high ransom demands, made BitPaymer stand out from other contemporary ransomware at the time. Though the encryption and ransom functionality of BitPaymer was not technically sophisticated, the malware contained multiple anti-analysis features that overlapped with Dridex. Later technical analysis of BitPaymer indicated that it had been developed by INDRIK SPIDER, suggesting the group had expanded its criminal operation to include ransomware as a monetization strategy.

The beginning of 2017 also brought a turning point in INDRIK SPIDER’s operation of Dridex. Dridex spam campaigns significantly declined, with new campaigns moving from high volume and frequency, to smaller, targeted distribution. The rapid development of Dridex also slowed during this time, with fewer versions released during 2017 than in previous years. CrowdStrike® Falcon® Intelligence™ also observed a strong correlation between Dridex infections and BitPaymer ransomware. During incidents that involved BitPaymer, Dridex was installed on the victim network prior to the deployment of the BitPaymer malware. Also unusual was the observation that both Dridex and BitPaymer were spread through the victim network using lateral movement techniques traditionally associated with nation-state actors and penetration testing.

These new tactics of selectively targeting organizations for high ransomware payouts have signaled a shift in INDRIK SPIDER’s operation with a new focus on targeted, low-volume, high-return criminal activity: a type of cybercrime operation we refer to as big game hunting. Since this shift, INDRIK SPIDER has used BitPaymer ransomware as a key vehicle for these operations, having netted around $1.5M USD in the first 15 months of ransomware operations.

Targeted Delivery

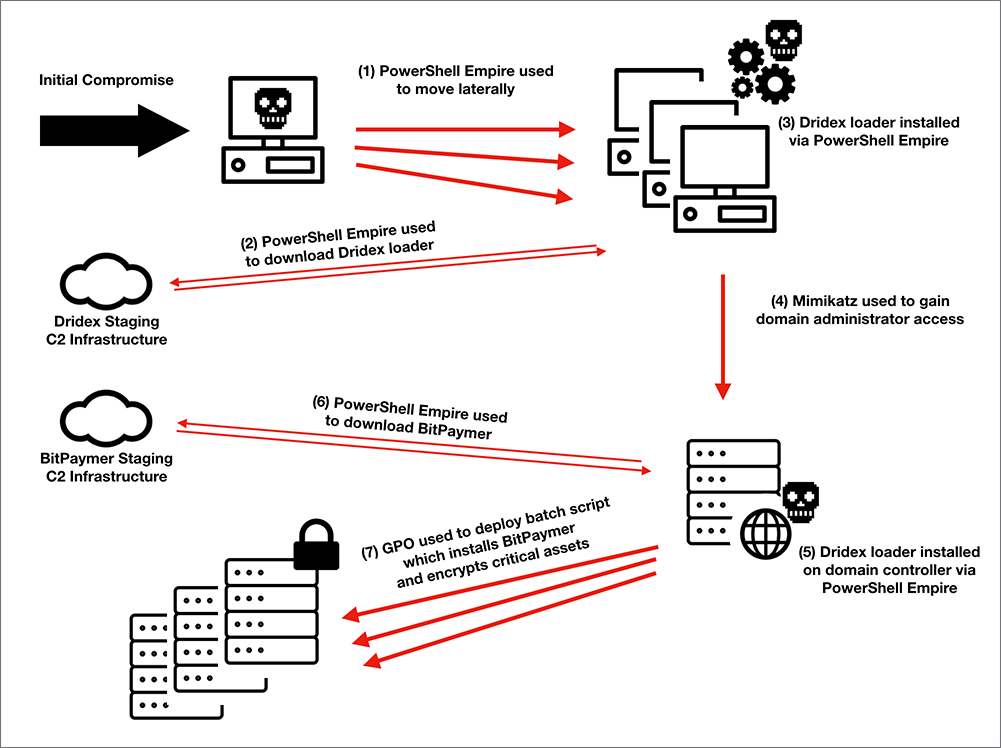

Falcon Intelligence has provided support to multiple active BitPaymer incident response (IR) engagements. The information gathered from these engagements, combined with information from prior Dridex IR engagements, provides insight into how INDRIK SPIDER deploys and operates both Dridex and BitPaymer. An overview of this process is provided below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. BitPaymer Ransomware Infection With Dridex

In recent BitPaymer IR engagements, Falcon Intelligence linked the initial infection vector to fake updates for a FlashPlayer plugin and the Chrome web browser. These fake updates are served via legitimate websites that have been compromised, and use social engineering to trick users into downloading and running a malicious executable. These fake update campaigns appear to be a pay-per-install service that is simply used by INDRIK SPIDER to deliver its malware, as other malware has also been delivered via the same campaigns.

Lateral Movement With PowerShell Empire

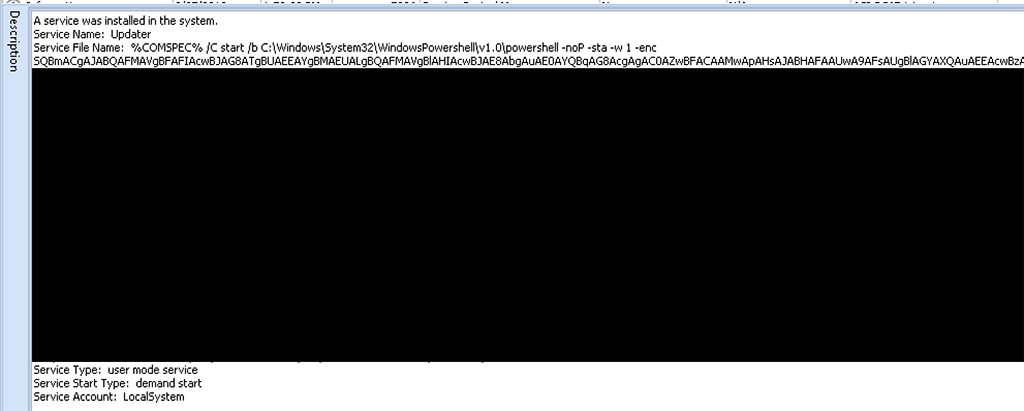

After the initial compromise, Falcon Intelligence observed both the Dridex loader and PowerShell Empire in operation on the infected host. PowerShell Empire is a post-exploitation agent built for penetration testing, which was used to move laterally between hosts. When moving between hosts, the PowerShell Empire agent was run as a service with the name Updater, as shown below in Figure 2.

Figure 2. PowerShell Empire Run as a Service

During this lateral movement, Falcon Intelligence also observed PowerShell Empire deploying the Mimikatz module on servers in the victim’s network. Mimikatz is a post-exploitation tool used to harvest credentials from Windows hosts. These compromised credentials were then used for further lateral movement. For many of the hosts that PowerShell Empire moved to, it would download and install the Dridex loader. The lateral movement continued until the domain credentials for the environment were retrieved and both PowerShell Empire and the Dridex loader were installed on the domain controllers in the environment. This process appears to be automated based on the speed at which the hosts are compromised.

Though traditionally used to load modules for fraud activity, recent updates to the Dridex loader also allow it to perform system and network reconnaissance. These reconnaissance capabilities include the ability to collect information about the current user on the host, list computers on the local network, and extract the system’s environment variables. This information is likely used to assist with identifying interesting targets within the victim network.

In some instances, Falcon Intelligence observed several days of inactivity between the time the domain controllers were compromised and the installation of BitPaymer. This delay may indicate that the operators were performing reconnaissance and gathering information about the victim before deciding how best to monetize the compromise.

Ransomware Deployed via PowerShell Empire and GPO

Falcon Intelligence has observed two different methods used to deploy BitPaymer once the domain controllers are compromised. In one instance, only the domain controllers and other critical infrastructure, like payroll servers, were targeted and PowerShell Empire was used to download and execute the BitPaymer malware directly on these servers.

In another instance, the BitPaymer malware was downloaded to a network share in the victim network, and a startup script called gpupdate.bat was pushed to all the hosts on the network via Group Policy Object (GPO), from the domain controllers. This script copied BitPaymer from the share and executed it on each host in the network, encrypting thousands of machines.

Big Game Hunters Use APT Tactics

This targeted deployment methodology involving credential compromise, lateral movement, and the use of system administrator tools closely mimics behavior Falcon Intelligence has observed from nation-state adversary groups, and penetration testing teams. With the move to targeting select victims for high-value payouts, the INDRIK SPIDER adversary group is no longer forced to scale its operations, and now has the capacity to tailor its tooling to the victim’s environment and play a more active role in the compromise with “hands on keyboard” activity.

BitPaymer Ransomware

Though the first publicly reported use of BitPaymer was in August 2017, when the malware was linked to ransomware attacks against several NHS hospitals, it was first identified in July 2017 by Twitter user Michael Gillespie. Later, in January 2018, a report was released that identified similarities between the BitPaymer ransomware and Dridex malware. The report authors renamed the malware “FriedEx.” Falcon Intelligence has analyzed this malware and can confirm the overlap between BitPaymer/FriedEx and Dridex malware.

Due to the targeted nature of the ransomware, BitPaymer is custom-built for each operation, with a unique encryption key, a ransom note and contact information embedded in it. As a result of this customization, there are multiple builds of the malware, though Falcon Intelligence has identified two main variants: an older variant that splits the encryption process into multiple “modes” with each mode focused on a specific task; and a newer variant that is built to be run as a service.

BitPaymer AKA “wp_encrypt”

During analysis, Falcon Intelligence obtained builds of the ransomware that contained the program database (PDB) string S:\Work\_bin\Release-Win32\wp_encrypt.pdb. Based on this string, the malware developers refer to this ransomware as wp_encrypt. The PDB string also contains the prefix string S:\Work\, which is identical to other Dridex modules, including those shown in Table 1. The ransomware also contains code from the Dridex modules, with some variants of the ransomware sharing up to 69 percent of their code with the Dridex loader.

| MODULE NAME | DESCRIPTION |

loader |

Downloads and installs the core Dridex modules, including the worker |

vnc |

Provides remote desktop access |

netcheck |

Checks network connectivity |

spammer |

Spam module |

worker |

Core component responsible for banking trojan functionality, including keylogging, web injects, download and execute second-stage payloads, etc. |

trendmicro |

Whitelists Dridex modules from TrendMicro antivirus detection |

wp_decrypt |

BitPaymer decryption tool |

Table 1. Dridex Modules Sharing the Same PDB Path Prefix

Anti-Analysis

Both variants of the BitPaymer malware feature multiple techniques to hinder analysis. The malware developers have employed a combination of encrypted strings, string hashes and dynamic API resolution to ensure that no strings exist in the binary.

Encrypted Strings Table

The BitPaymer malware contains a small table of encrypted strings in the rdata section of the binary. These strings use standard RC4 encryption in which the first 40 bytes form the RC4 key, and the remaining data contains the encrypted strings table. These strings are temporarily decrypted on-demand during runtime. The strings in the decrypted strings table are separated by a null byte and are referenced by their order. This string table encryption method is identical to the method used in other Dridex malware, including the 40-byte key length and the position of the table in the rdata section. The strings table includes, among other strings, the RSA public key used in the ransomware encryption, the ransom note, file extensions and the encryption target flags string.

String Hashes

In addition to the encrypted strings table, BitPaymer replaces the remaining strings in the binary with hashes and uses an algorithm to match these hashes with strings that exist on the host. For example, when setting the run key for persistence, instead of simply opening the registry key HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run, BitPaymer uses the API RegEnumKeyW to iterate through all the registry keys, comparing their hash value until the correct key has been located. The hashing algorithm generates a CRC32 hash of the string, converted to lowercase. This hash is combined with a DWORD using a simple XOR. This DWORD is different for each build of the malware. This string hashing algorithm is identical to the hashing algorithm used in other Dridex modules. The hash algorithm has been replicated in Python below.

import binascii

def get_string_hash(string_value, key_dword):

crc_hash = binascii.crc32(string_value.lowercase()) & 0xffffffff

hash_value = crc_hash ^ key_dword

return hash_value

Dynamic API Resolution

The Windows APIs that are used in the malware are resolved dynamically at runtime. For each API, the function name and DLL name are hashed and stored in the binary. At runtime, when the API is needed, the malware will iterate through all DLLs in the Windows system directory, comparing a hash of their name with a precomputed DLL hash until it has been located. The malware will then load the DLL and iterate through the export table comparing a hash of the API name with the expected hash until it has been located. The hashing algorithm used for the API names is the same CRC32 algorithm used for the string hashes. However, when hashing the DLL names, BitPaymer converts the strings to uppercase before hashing them. This process is also used in other Dridex modules.

Persistence

The older “mode” variant of BitPaymer uses the Windows registry for persistence, while the newer service variant will attempt to install itself as a service. If that fails, it will fall back to using the Windows registry.

Registry Persistence

The older “mode” variant will first copy itself to either the %USERPROFILE%\AppData\Local or the %USERPROFILE%\AppData\LocalLow directory, depending on its process integrity level. Then it will add a new registry value to the registry key HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run with the path to the newly copied malware. The registry value name is a randomly generated string between five and fifteen characters, containing upper and lowercase letters as well as numbers.

Windows Event Viewer UAC Bypass (eventvwr.msc)

When the newer service variant of BitPaymer is run, it first determines if it is being executed from an alternate data stream. If it is not executed from an alternate data stream, the malware creates a file in the %APPDATA% folder with a random file name between three and eight characters long, containing uppercase and lowercase letters as well as numbers. It then copies itself to the alternate data stream :bin of the newly created file and creates a new process from the stream.

When the malware is executed from the alternate data stream, it checks the process integrity level. If it is not running with a level above medium integrity, it attempts to elevate its privileges. To suppress the User Access Control (UAC) prompt that normally occurs during privilege elevation, the malware uses a UAC bypass technique first documented in August 2016. This bypass requires temporarily setting either the registry key HKCU\Software\Classes\ms-settings\shell\open\command on Windows 10, or the registry key HKCU\Software\Classes\mscfile\shell\open\command on Windows 7 to execute the malware. Once the registry key is set, the malware launches the Windows event viewer process eventvwr.msc, which will inadvertently launch the malware set in the registry keys with elevated privileges.

Hijacked Service Persistence

If elevated privileges are not obtained, the malware falls back to using the same Windows registry run key as the older mode variant for persistence HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run. However, if the malware is successful in elevating privileges, it begins to enumerate existing Windows services on the host that are configured to run as LocalSystem. The malware selects services that are currently not active and ignores services that launch the executables svchost.exe and lsass.exe. For each service, the malware attempts to take control of the service’s executable — first using icacls.exe with the /reset flag to reset the executable’s permissions, then using takeown.exe with the /F flag to take ownership of the executable.

If this is successful, the malware creates a :0 alternate data stream in the executable and copies the executable’s own contents to the stream. This can be used to restore the executable later. Then the malware replaces the contents of the executable with a copy of itself and launches the service. The file modified time of the executable is also artificially changed to 00:00:00 UTC. The purpose of this time change is so the file can be identified and restored by the decryption tool.

Once a service has been successfully hijacked and launched, the malware stops attempting to hijack the remaining services and exits. If there are no services matching the selection criteria, BitPaymer simply exits and no files are encrypted

Shadow Files Removal

Before encryption, both variants of BitPaymer attempt to remove the backup shadow files from the host, making it impossible to restore encrypted files. This is achieved by launching the vssadmin.exe process with the following command vssadmin.exe Delete Shadows /All /Quiet.

Encryption

There is a string present in the strings table that works like a configuration flag for the encryption targets of the malware. The string may contain a combination of the letters F, R, N, and S. During the encryption process, the letters in this flag are checked to determine what drive types to encrypt. The corresponding drive types for each letter are described below in Table 2. All BitPaymer samples analyzed by Falcon Intelligence had all four flags enabled for maximum encryption.

| LETTER | DESCRIPTION |

| F | Encrypt fixed drives |

| R | Encrypt removable drives |

| N | Encrypt network drives (mounted) |

| S | Search for network shares on the domain / workgroup and encrypt them |

Table 2. BitPaymer Drive Type Configuration String

Network Share Encryption

In order to encrypt network shares, BitPaymer will attempt to enumerate the sessions for each user logged onto the infected host and create a new process, using the token of each user. These new processes will first spawn a net.exe processing with the view argument to gather a list of network accessible hosts. For each host, BitPaymer spawns another net.exe process with command net view <host> using the newly discovered host as a parameter. This will return a list of network shares available to the impersonated user on the host. Once a list of all available shares has been gathered, BitPaymer attempts to mount them to be encrypted.

Encryption Routine

For each drive targeted, the malware recursively iterates through all files and directories. For each file, the name and path are compared against a list of excluded filenames and two lists of excluded directory names. These exclusion lists are composed of regular expression type strings that are located in the encrypted strings table. If the file name and path do not match any regular expressions in the exclusion lists, the file is encrypted.

The file encryption algorithm imports a hard-coded RSA 1024-bit public key from the encrypted strings table using CryptImportPublicKeyInfo, and for each file, generates a 128-bit RC4 key using CryptGenKey. The RC4 key is then used to encrypt the file in place. Once it is encrypted, the file is moved to a new file with the same name, and the file extension is appended with the keyword .locked.

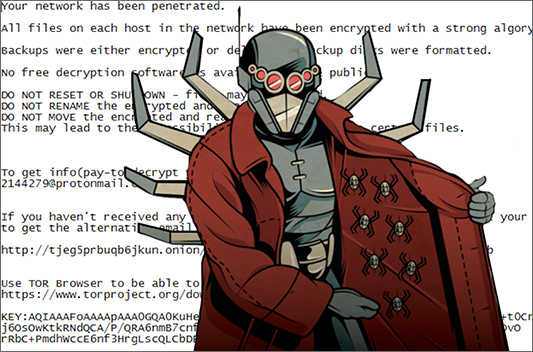

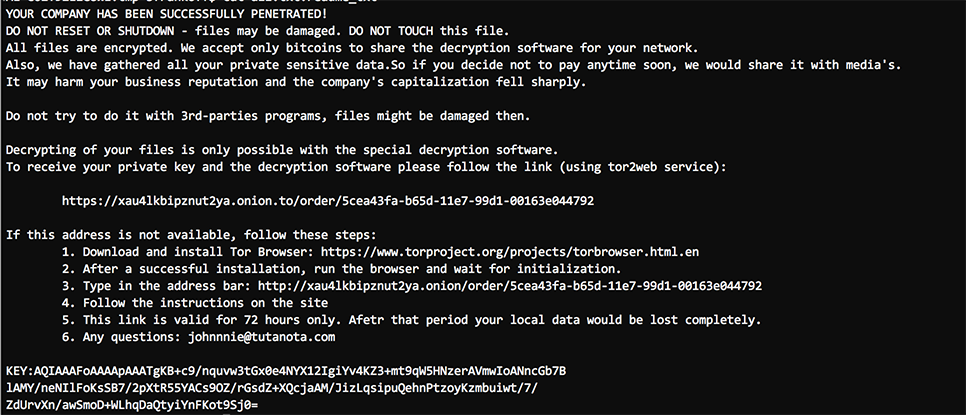

The RC4 key is exported as a SIMPLEBLOB encrypted with the RSA key and Base64-encoded. A second file is created with the same name as the encrypted file, except it is appended with the extension .readme_txt. A ransom note is written to this file, and the RSA-encrypted, Base64-encoded RC4 key is appended to this file along with the KEY: string. An example of the ransom note with the appended key is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. BitPaymer Ransom Note with Encrypted RC4 Key

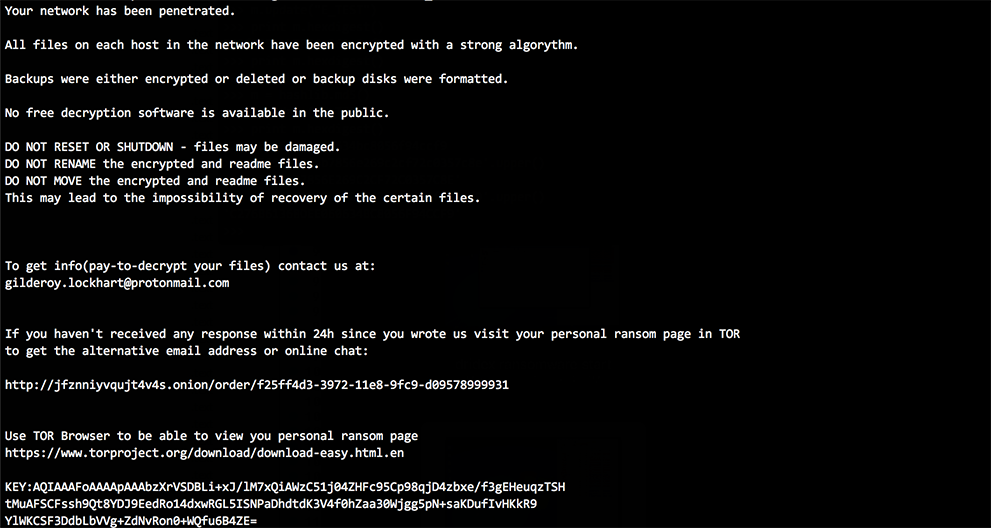

Because the key is not appended to the encrypted file but instead written to a separate file, if the file containing the ransom note is accidentally deleted or moved to a separate directory, the encrypted file will become unrecoverable. There is some indication that this may have occurred in the past, as newer ransom notes include specific warnings about touching the readme_txt files, while older versions of the ransom notes do not. The text from a newer ransom note is provided below in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Newer Version of BitPaymer Ransom Note

The language in the ransom notes indicate that this ransomware is targeted specifically at companies, not individuals. The notes also contain a threat to leak private information that has been collected from the target if the ransom is not paid. Though there is no functionality to collect this information in the ransomware itself, the ransomware is deployed by INDRIK SPIDER in parallel with Dridex malware, and the Dridex malware contains modules that may be used to collect information from infected hosts.

The use of an embedded RSA public key also indicates that each build of the ransomware binary is unique to a specific target. By design, the decryption tool needs to contain the corresponding RSA private key so if the same build is used for multiple targets, the ransom would only need to be paid once to acquire the private key, which could then be used to decrypt all the infections. Falcon Intelligence has acquired multiple decryption tools related to BitPaymer, which confirm the theory that a unique key is used for each infection.

Ransom Note and Decryption Process

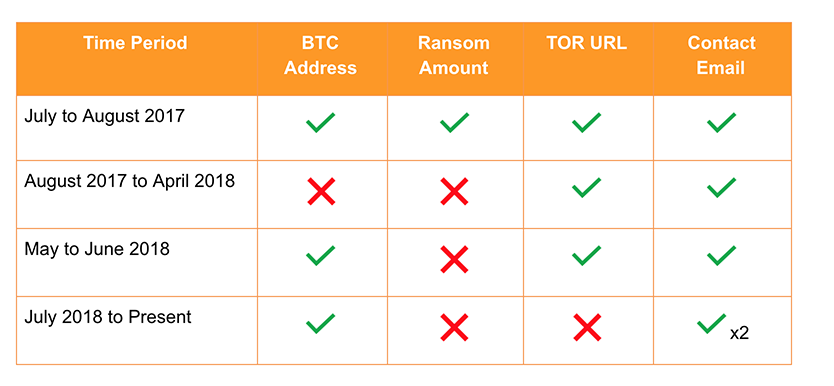

Information provided in Bitpaymer ransom notes has continued to change, with the first change coming shortly after the first identified campaign in July 2017. Initially INDRIK SPIDER provided all required information in either the ransom note or through a TOR-based payment portal, meaning the victim could make the payment with very little interaction with the actor. However, later notes removed this key information forcing the victims to email the INDRIK SPIDER campaign operator for payment and decryption details. A table of observed ransom note changes can be seen below.

Table 3. BitPaymer Ransom Note Changes

By removing the ransom demand from the note, INDRIK SPIDER can change the amount based on campaign success, which likely depends on the size of the organization and the speed of initial contact from the victim.

Email Support for Decryption

Unlike many ransomware operations, which usually just require victims to make the payment and subsequently download a decryptor, INDRIK SPIDER requires the victim to engage in communication with an operator. Falcon Intelligence has had unique insight into the email dialogue between a victim and an INDRIK SPIDER operator. This dialogue has revealed details about how the adversary approaches payment negotiation with the victim, as well as the communication of decryption instructions.

Initial victim communication with the INDRIK SPIDER operator, using one of the email addresses provided, results in the operator providing key pieces of information up front, such as the BTC address and the ransom amount. INDRIK SPIDER is also willing to demonstrate decryption legitimacy by offering to decrypt two test files of the victim’s choice.

It was made clear during communications that INDRIK SPIDER is not willing to negotiate on the ransom amount, explicitly stating that the victim can use multiple Bitcoin exchanges to obtain the number of BTC required, and the exchange rate should be calculated based on the rate posted on the cryptocurrency exchange Bittrex.

Ransom demands have varied between requesting an exact USD value in BTC and an exact number of BTC, which is likely due to the continued fluctuation in the BTC-to-USD value. In communications with INDRIK SPIDER, the victim is told to use any BTC exchange from the top 10 and seek help from local information technology (IT) support companies. Of note, INDRIK SPIDER specifies the geographical location of where the victim should seek help, confirming that they know key information about the victim.

Once payment has been made, INDRIK SPIDER acknowledges receipt and states that the decryptor will be “delivered within a few hours.” Though earlier in the communication process, a one-hour time window for delivery of the decrypter is promised upon receipt of payment, the decryptor was actually delivered closer to four hours after payment. This discrepancy could be due to the difference in time zones and working hours of the INDRIK SPIDER operator.

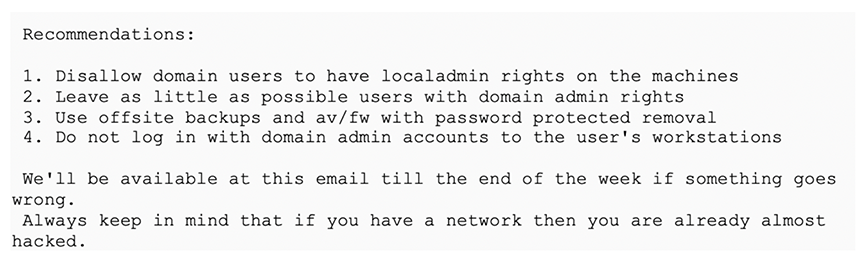

INDRIK SPIDER uses file sharing platforms to distribute the BitPaymer decryptor. In an extensive email to the victim, the INDRIK SPIDER operator provides a decryptor download link, decryptor deletion link (to be used following decryptor download) and a password. The same email also provides clear instructions on how to download and use the BitPaymer decryptor, including how to remove the malware persistence. The operator also states that they will be able to provide assistance using the same email address for a further period of time, which is usually until the end of the current work week. Interestingly, INDRIK SPIDER provides the victim with several key security recommendations to follow that may ultimately avoid further breaches (see Figure 5). The recommendations provided are not only good advice, but also provide indications of how INDRIK SPIDER breaches organizations and moves laterally until domain controller access is gained.

Figure 5. BitPaymer Security Recommendations

Ransom Payments

Ransom demands have varied significantly, suggesting that INDRIK SPIDER likely calculates the ransom amount based on the size and value of the victim organization. The lowest identified payment was for approximately $10,000 USD, and the highest observed was for close to $200,000 USD.

| BTC Address | Total Received in USD |

12AWdHJkwF193ud21XWGontyCJTW6A9i6p |

$197,596.05 |

1Ln9RxSRuDqqFhCTuqBPBKRMeyhVhRaUG4 |

$0 |

1BWj247jtipKr1wuFciKypeidZVwZWHCi9 |

$77,651.59 |

19aF868XPJhNqheXWgvrHPqnXpwhttf3Hw |

$173,315.48 |

14uAWnPnhtrXDB9DTBCruToawM65dUgwot |

$740,752.71 |

1PNmBWJHzJGqTUemastR7E4ccrUNASktmZ |

$172,793.80 |

1DWbPyjmbKA1NFqv3nyL47y9Vsz6WFU4Hw |

$192,867.22 |

Table 4. BitPaymer BTC Addresses and Identified Payment Totals

As of Nov. 1, 2018, Falcon Intelligence had observed a total of 185.7 BTC paid to INDRIK-SPIDER-controlled BTC addresses, with a USD total of $1,554,977 based on BTC-to-USD value at the time the ransom payment was made.

How CrowdStrike Falcon® Prevent Stops BitPaymer

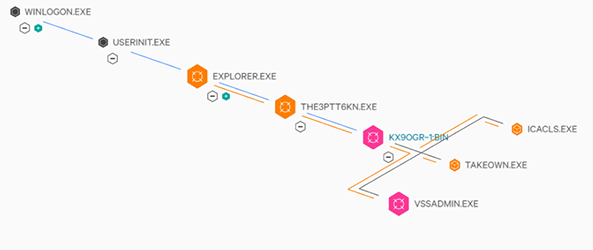

The process tree for BitPaymer, as seen by the Falcon sensor, is shown below in Figure 6. To prevent BitPaymer from encrypting files on the host, Falcon Prevent™ next-generation antivirus must kill the ransomware process (KX9OGR~1:BIN) prior to execution of the file encryption routines.

Figure 6. BitPaymer Process Tree

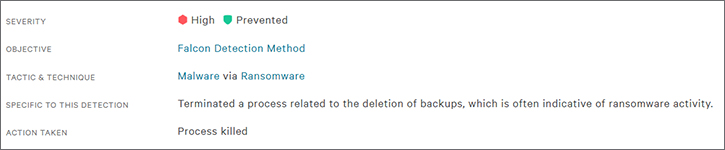

Falcon Prevent provides two layers of defense to protect against ransomware threats like BitPaymer: indicators of attack (IOAs) and machine learning (ML). Either one of these defenses is enough to stop the BitPaymer process before it can encrypt any files.

Figure 7 below shows an example of an IOA prevention alert that is sent to the centralized Falcon console. In this case, BitPaymer’s attempt to delete the backup shadow files triggered the IOA that led to the prevention of this process.

Had a prevention not existed for this IOA, BitPaymer would still have been prevented with CrowdStrike Falcon®’s ML. Below, Figure 7 shows CrowdStrike ML detecting the BitPaymer binary as malicious.

Figure 7. BitPaymer Prevented by Falcon Prevent

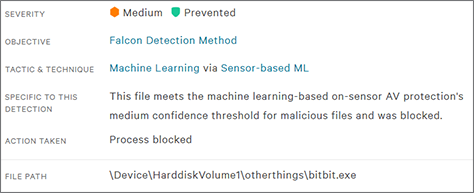

Had a prevention not existed for this IOA, BitPaymer would still have been prevented with CrowdStrike Falcon®’s ML capabilities. Below, Figure 8 shows CrowdStrike ML detecting the BitPaymer binary as malicious.

Figure 8. BitPaymer Detected by CrowdStrike Machine Learning

The Future of INDRIK SPIDER and Big Game Hunting

INDRIK SPIDER consists of experienced malware developers and operators who have likely been part of the group since the early days of Dridex operations, beginning in June 2014. The formation of the group and the modus operandi changed significantly in early 2017. Dridex operations became more targeted, resulting in less distribution and Dridex sub-botnets in operation, and BitPaymer ransomware operations began in July 2017.

There is no doubt that BitPaymer ransomware operations are proving successful for this criminal group, with an average estimate take of over $200,000 USD per victim, but it is also important to remember that INDRIK SPIDER continues to operate the Dridex banking trojan. Though Dridex is still bringing in criminal revenue for the actor after almost four years of operation, targeted wire fraud operations likely require lengthy planning. Therefore, a ransomware operation provides high-value income for the actor for a lot less expenditure, both in operator and development costs.

Falcon Intelligence anticipates that INDRIK SPIDER will continue to operate both Dridex and BitPaymer, with the two monetization strategies complementing each other. In scenarios where wire fraud is not as lucrative an option, INDRIK SPIDER might use ransomware to monetize the compromise instead. What is clear though, is that the low-scale, selective targeting and high payout tactics of big game hunting is proving to be a winning strategy for INDRIK SPIDER.

INDRIK SPIDER isn’t the only criminal actor running big game hunting operations; The first ransomware to stake a claim for big game hunting was Samas (aka SamSam), which is developed and operated by BOSS SPIDER. Since they were first identified in January 2-16, this adversary has consistently targeted large organizations for high ransom demands. In July 2017, INDRIK SPIDER joined the movement of targeted ransomware with BitPaymer. Most recently, the ransomware known as Ryuk came to market in August 2017 and has netted its operators, tracked by Falcon Intelligence as GRIM SPIDER, a significant (and immediate) profit in campaigns also targeting large organizations.

Falcon Intelligence anticipates that big game hunting operations will continue to grow. The criminal actors INDRIK SPIDER, BOSS SPIDER, and GRIM SPIDER will sustain their operations in the near-term. It is also likely that other criminal actors are considering the option of running sophisticated ransomware operations. Given the tools, skilled campaign operators and malware required, it is likely there will still be only a handful of criminal groups able to do so in the near future; however, Falcon Intelligence considers this to be a growing eCrime threat.

Indicators

The following table contains SHA256 hashes for BitPaymer samples analyzed by Falcon Intelligence.

| SHA256 Hash | Build Time (UTC) |

c7f8c6e833243519cdc8dd327942d62a627fe9c0793d899448938a3f10149481 |

2017-10-22 07:48:04 |

17526923258ff290ff5ca553248b5952a65373564731a2b8a0cff10e56c293a4 |

2017-06-08 14:20:38 |

282b7a6d1648e08c02846820324d932ccc224affe94793e9d63ff46818003636 |

2017-06-30 09:33:52 |

8943356b0288b9463e96d6d0f4f24db068ea47617299071e6124028a8160db9c |

2018-01-26 14:43:27 |

The following table contains SHA256 hashes for unpacked BitPaymer decryptor samples analyzed by Falcon Intelligence.

| SHA256 Hash | Build Time (UTC) |

f0e600bdca5c6a5eae155cc82aad718fe68d7571b7c106774b4c731baa01a50c |

2017-06-07 15:08:59 |

b44e61de54b97c0492babbf8c56fad0c1f03cb2b839bad8c1c8d3bcd0591a010 |

2017-08-02 15:40:03 |

13209680c091e180ed1d9a87090be9c10876db403c40638a24b5bc893fd87587 |

2017-11-07 14:40:50 |

The following table contains SHA256 hashes for Dridex samples deployed during the initial stages of a BitPaymer compromise.

| SHA256 Hash | Build Time (UTC) |

91c0c6ab8a1fe428958f33da590bdd52baec868c7011461da8a8972c3d989d42 |

2018-05-01 14:43:04 |

f1d69b69f53af9ea83fe8281e5c1745737fd42977597491f942755088c994d8e |

2018-05-01 00:35:47 |

39e7a9b0ea00316b232b3d0f8c511498ca5b6aee95abad0c3f1275ef029a0bef |

2018-02-18 12:38:40 |

Learn More:

- For more information on how to incorporate intelligence on threat actors like INDRIK SPIDER into your security strategy, please visit the Falcon Intelligence product page

- Download the CrowdStrike 2020 Global Threat Report

- Learn more about CrowdStrike’s next-gen AV solution

- Test Falcon Prevent for yourself with a free 15-day trial today