Understand CNAPPs with Our Guide

Understand CNAPPs with Our Guide

There are a lot of concepts that you need to master at the beginning of your DevOps career. Some are endemic to a single cloud or service provider; others, just like the topic of this article, universally extend throughout the entire industry.

This post will discuss virtual private clouds, or VPCs—what they are, how they work, and why they are a staple of today’s cloud infrastructure.

The Basics of VPCs

What exactly is a VPC? If you’ve ever seen a movie featuring a typical camera shot of a bank vault, there’s usually a large secured room with many separate safety deposit boxes.

A VPC is a single compartment within the entirety of the public cloud of a certain provider, essentially a deposit box inside the bank’s vault. The vault itself is public, with many customers of the bank accessing it from time to time; they may even have boxes in the same vault as you. But for them, your drawer is untouchable, or even invisible; only you have the key to open it, meaning no one else can access it unless you wish them to.

Of course, with a VPC, the “bank” - AWS, Google Cloud, or Azure - is far away, maintained by a literal horde of engineers, and the boxes are separated not by reinforced steel but logical features.

On AWS and GCP, the VPC is called a VPC; on Azure, it’s actually called a VNet (Azure Virtual Network); They all implement similar features and security measures.

Features & Isolation

A VPC provides you a place to deploy services and offerings of the public cloud with tight access control. It can cover multiple regions and their availability zones, allowing you to deploy infrastructure closer to your customers or protect against a failure in a single location.

The subject of isolation comes up quite often, and that’s because it's actually the most important feature of all. Your data is separated from the data of other customers. Whatever you decide to be isolated is isolated from the outside, and access to the deployed resources can be easily kept to only those you designate.

The most commonly used mechanisms of isolation are public/private subnets, security groups, and access control lists, all of which we’ll talk about below.

The Benefits

How does choosing a VPC over the public cloud benefit you? There’s a lot of good you can squeeze out from being a separate entity governed by your rules, yet also a part of the “bigger picture,” protected by your chosen cloud provider.

As always, security comes first. You’re given access to plenty of solutions you’d expect from a traditional public cloud, but with much more flexibility. Additional observability tools, granular access control, and the multitude of safeguards and mechanisms embedded into the concept itself contribute greatly toward the security and privacy of your infrastructure and data.

Another benefit is that VPCs are much cheaper than a traditional private cloud, yet they give you many features you’d have to pay quite a lot for.

Resources available for deployment inside a VPC are the usual offerings of the public cloud, so, by extension, just as with the public clouds, you can scale things up cheaply and easily.

Configuration — Network ACLs, Security Groups & Subnets

Properly configuring access to your VPC is entirely up to you, as maintaining data isolation is critical. That means you have to get it right, every time. These mechanisms will help you do that.

Subnets

Subnets are the most traditional way of separating network objects. If you’ve ever configured a router at home, or worked with any kind of networks, you’ve definitely run into these. In essence, it’s a block of IP addresses that you can allocate to your resources. It’s derived from the main network pool of your VPC—kind of a “slice of a slice” situation.

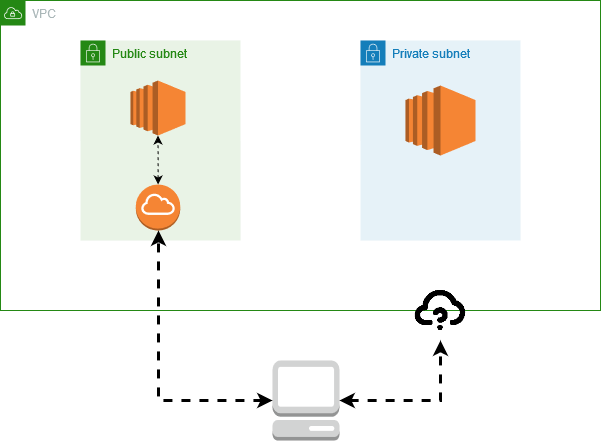

There are two typical flavors of subnets: private and public. A private subnet is cut off from the internet, unless you provision a NAT device to act as a “translator” of sorts.

A public subnet can reach the web, usually with the help of an internet gateway acting as an intake/output valve. The gateway provides an IP address that is externally reachable, giving you a point that you can connect to.

A public subnet, reachable from the web, and a private one that you cannot reach from outside.

A public subnet, reachable from the web, and a private one that you cannot reach from outside.Network ACLs

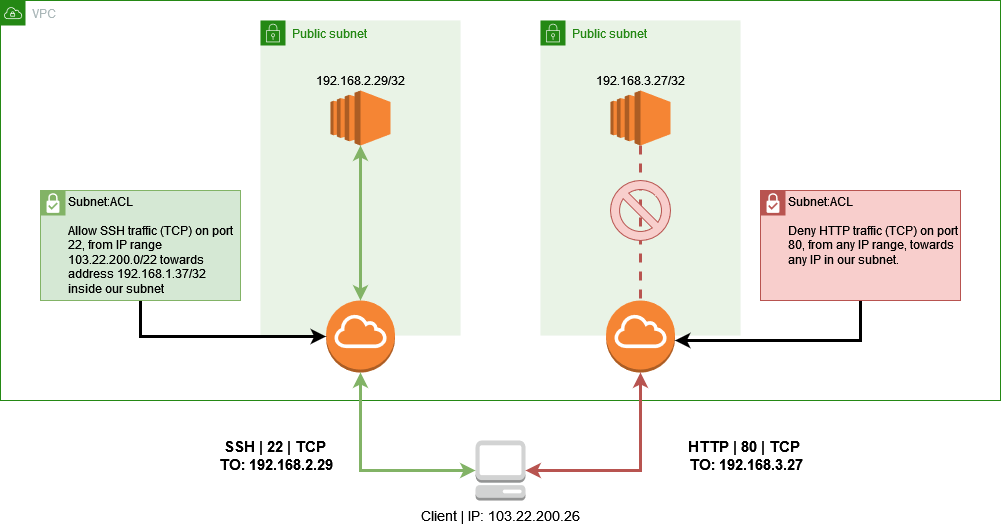

A Network ACL is an additional part of the subnet’s logic; it acts as an ordered ledger of rules regarding which type of traffic can go in/out, through which port, and even from where/to where. Take a look at the following example:

A typical scenario of subnet ACLs in practice. Left request will succeed; The right one will time out.

A typical scenario of subnet ACLs in practice. Left request will succeed; The right one will time out.Something you should always keep an eye on is the order of these rules. They are processed from lower to higher numbers, and if a match is found, it is applied regardless of anything a rule with a higher number might say. This is very easy to overlook, and even a small mistake could allow for a leak to occur.

Security Groups

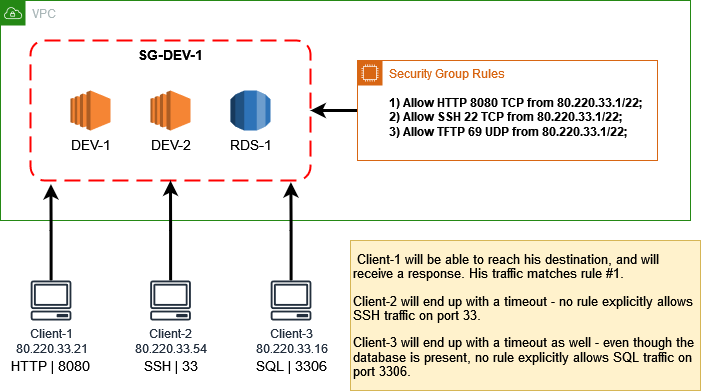

Security groups take a different approach; instead of controlling certain subnets, they operate on resources such as instances. In contrast to network ACLs, you cannot explicitly create a “deny” rule; security groups consider anything that isn’t defined as allowed to be forbidden by default. You also don’t have to explicitly allow response traffic; if something flows in, the response is allowed to flow out.

The order of rules specified for a security group doesn’t matter either; the entire set of rules is evaluated when the traffic arrives. You can attach multiple security groups to a resource, and (at least with AWS) if you don’t, the default one is automatically attached for you.

Example of security group rules controlling access to a set of resources.

Example of security group rules controlling access to a set of resources.Luckily, the question of which access control method you should use isn’t very hard to answer. You should use all of them. In general, putting as many layers as you can between you and the dark, cold space of the World Wide Web is a good practice—one that you should definitely take to heart.

VPCs in Practice — 4 Takeaways

Below are four tips to help you get the best out of your VPC with less hassle.

1. AWS provides you with a default VPC, when your account setup is done; although it’s technically ready to use, go through the security settings mentioned above and make sure that they align to your needs to avoid any nasty surprises. Additional heads-up for Terraform operators; the default VPC resource crucially differs from a typical one!

2. Provisioning a VPC is trivial; however, managing security groups and network ACLs gets complicated as they grow in rule count. Watch out, if you don’t want to get buried under a ton of unreadable rules, or let something sneak in through a long-forgotten gap.

3. If you’re using security groups and network ACLs to allow access to your environments for your teammates or co-workers, make sure that the addresses you whitelist are either static or updated very, very frequently. Otherwise, one day, an allowed address might suddenly end up in the hands of a malicious actor who won’t mind snooping around. This can be resolved in multiple ways, including a company-controlled private VPN (a typical public one would be subject to the same risk of IP reassignment!) or tools like HashiCorp Boundary.

4. The number of VPCs you can provision on pretty much every public cloud is limited. If you want to provide customers with their own tenant spaces, unless it’s in microscale, other solutions (IAM identities, additional user accounts, etc.) will prove to be a much better alternative.