Making the world a better place has always been a core goal of CrowdStrike. In this blog post, we are making our findings, and tools, for decrypting NotPetya/Petya available to the general public. With the aid of the supplied tools, almost all of the Master File Table (MFT) can be successfully recovered within minutes.

Decryption of the MFT

The MFT is inarguably one of the most crucial data structures of an NTFS file system. It contains the list of files in the file system together with metadata such as dates, file size, location on disk, etc. Without the MFT, any attempt to recover files is almost impossible. Decryption of the MFT is only possible by exploiting several weaknesses in the NotPetya/Petya implementation of the Salsa20 cipher. Basically, it’s a combination of a known-plaintext attack and a many-time pad attack. Note that this attack does not mean Salsa20 is broken, it only affects this specific implementation.

How Can I Decrypt the MFT?

To recover the MFT, first, it needs to be extracted from an infected hard disk. This can be done by either having a forensic disk image, by attaching the infected hard drive to a non-infected system, or by booting the infected computer from a live CD<1>. Assuming the first case, i.e., a forensic disk image with the name disk.dd has been acquired, the following set of commands will extract the MFT to the file mft.raw:

Slot

Start

End

Length

Description 000: Meta 000000000000000000000000000001Primary Table (#0) 001:

-------000000000000000020470000002048Unallocated 002:000:000000000204802029588470202956800NTFS / exFAT (0x07)

The first command, mmls, returns the partition layout. Commonly, the start sector of the main NTFS partition is either 63 or 2048. The next command, icat, outputs the MFT of the NTFS partition to mft.raw. Once the encrypted MFT has been extracted, it can be decrypted with the tool decryptPetya.py from the CrowdStrike repository.

--mft mft.rawDepending on the size of the MFT and how many records are encrypted, decryption takes about 2-30 minutes. The command line options for decryptPetya.py are:

--help

show this help message and exit

--mft MFT, -m MFTMFT filename

--strict, -s

Do a strict decryption: only output MFT records that

can be decrypted with high confidence. Others are marked

as bad.

The script outputs the decrypted MFT under the file name .decrypted_strict or .decrypted_relaxed, depending on the supplied option. By default, the relaxed decryption is chosen. It tries to decrypt a given ciphertext even if the confidence is relatively low. For a forensically sound analysis the threshold is chosen in a way to maximize confidence in the results. This can be done by selecting the “--strict" option.

Manual Analysis of Decrypted MFT Records

In rare cases, it might be necessary to recover the first or last few MFT records. This can be done with the aid of the log file decryptPetya.log. To that end, the log file outputs the most probable plaintext for a given ciphertext. The following log excerpt gives an example:

In the default use case, decryptPetya.py already fills in the most probable byte. In this case, the most probable byte 0x00 with a certainty of 0.9876 is automatically written to the decrypted record.

Further Analysis of the MFT

Once satisfied with the MFT, it can be further analyzed, for example with tools like analyzeMFT.py, or patched into the HDD.

Technical Details

What mistakes did the Petya author make (and were later copied by the NotPetya authors) that allow for a decryption of the MFT? Previous reporting on Petya and NotPetya variants showed that they share a faulty implementation of the Salsa20 cipher <2>. The code bears remarkable resemblance to an open-source implementation that can be found on GitHub <3>. While the source code of this implementation is correct, the Petya authors made several mistakes during the transition to 16-bit code. These mistakes make all Petya/NotPetya versions vulnerable to a known-plaintext attack that allows for the decryption of large parts of the MFT.

Salsa20 Stream Position Weakness

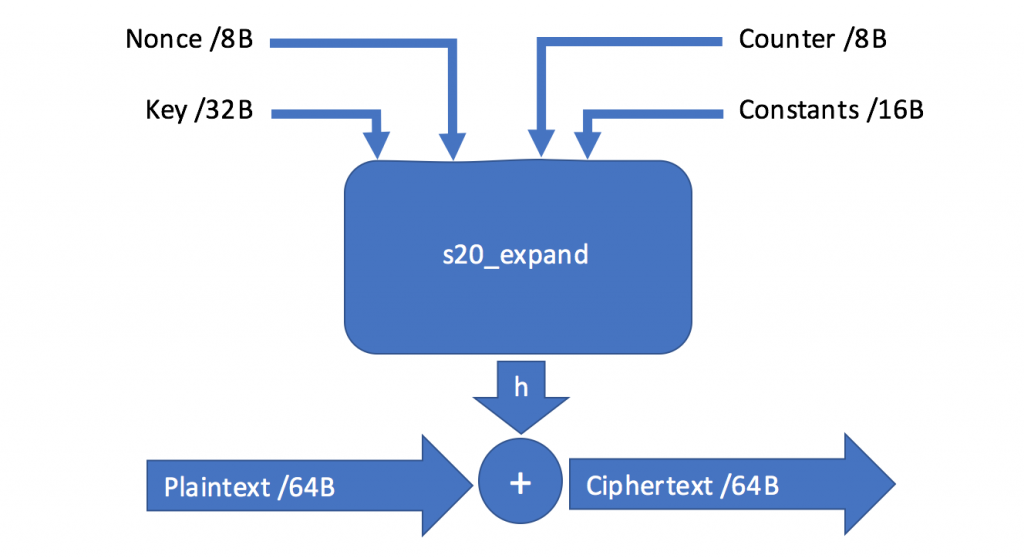

This section describes a weakness in the way the stream position is used by NotPetya/Petya. Instead of using the byte offset in the stream of data to be encrypted, NotPetya/Petya uses the number of the respective sector, which has significant consequences for the security of the scheme. NotPetya/Petya uses a modified version of Salsa20, a symmetric stream cipher that maps a 256-bit key, a 64-bit nonce, and a 64-bit stream position to a 512-bit block of the key stream. The main encryption function is called s20_crypt(). Due to the position argument, this algorithm provides a unique ability to seek to an arbitrary offset in the key stream in constant time. The algorithm relies on a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) to produce a keystream that is applied in a byte-wise XOR operation to the plaintext. The following figure gives an overview of the Salsa20 algorithm:  The Salsa20 PRNG function, called s20_expand(), is initialized with four input parameters: 1.)

The Salsa20 PRNG function, called s20_expand(), is initialized with four input parameters: 1.)

A constant (-1nvalid s3ct-id), in contrast to the original algorithm’s constant (expand 32-byte k) 2.)

A 32-byte randomly generated key 3.)

As shown in red, the same variable is used to read a sector from disk and as stream offset for the s20_crypt() function. The sector number is then used as input to the PRNG function s20_expand(), as shown in the following disassembly listing:

The fact that the sector number is used instead of the actual stream position (in bytes) makes all NotPetya/Petya versions vulnerable to a known-plaintext attack. Consider the example with the following parameters: 32-byte key:

Nonce:

Next encrypted sector number: 0x00600061 The s20_expand_key() function is invoked with sector number divided by 64, i.e., 0x18001. This results in the following key stream:

AC 1E 1D 43 CF B7 FD 48 91 72 7A CD 06 33 BB C6000010

2E FF CA 4F F9 DB 09 F6 21 5F 87 96 BD 49 9E 66 000020

74 FF D7 83 CF B2 E0 EC C1 7A 6B 9D EA 64 3B 82 000030

42 90 65 06 E9 E1 10 87 DF BC FA 0B 4F FD E0 39

The index of the key stream is calculated by the modulus operator of the sector number: 0x00600061 % 0x40 = 0x21 Hence, the actual XOR stream starts at index 0x21 of the key stream:

FF D7 83 CF B2 E0 EC C1 7A 6B 9D EA 64 3B 82 42 000010

90 65 06 E9 E1 10 87 DF BC FA 0B 4F FD E0 39 77 <...>

Next, the sector 0x00600062 is encrypted. Since the sector number is only increased by one, the resulting XOR key stream is:

D7 83 CF B2 E0 EC C1 7A 6B 9D EA 64 3B 82 42 90000010

65 06 E9 E1 10 87 DF BC FA 0B 4F FD E0 39 77 CE <...>

Therefore, if NotPetya/Petya encrypts sector i, and the resulting 64-byte key state is FF D7 83 CF <...>, the key state for sector i+1 would be D7 83 CF B2 <...>. This insight can be used to attack the NotPetya/Petya cryptography with a known-plaintext attack. The reason behind this is the keystream can be trivially extracted once a piece of plaintext is known. Let x denote the plaintext and k the keystream, then E(x) = x ⊕ k. If x is known, the key can be recovered by applying XOR once again: E(x) ⊕ x = (x ⊕ k) ⊕ x = k. This procedure exploits the commutative and associative properties of XOR. Once the keystream is known, other parts of the ciphertext can be decrypted.

Exploiting the Stream Position Weakness

In the above section, we showed that if we have certain knowledge about underlying plaintext, we can easily calculate the original keystream by XORing the ciphertext with the plaintext. Due to the repetitive nature of the keystream, this knowledge can be exploited to derive large portions of the keystream. First, the MFT needs to be decrypted. It is an almost ideal data structure for a known-plaintext attack. In the general case, the MFT comprises a contiguous list of MFT records. Each MFT record has the following structure:

| Offset | Size | Description |

| 0x00 | 4 | Record signature |

| 0x04 | 2 | Offset to update sequence |

| 0x06 | 2 | Number of entries in Fixup array |

| 0x08 | 8 | $LogFile sequence number (LSN) |

| 0x10 | 2 | Sequence number |

| 0x12 | 2 | Hard link count |

| 0x14 | 2 | Offset to first attribute |

| 0x16 | 2 | Flags: 0x01: record in use

0x02: directory |

| 0x18 | 4 | Actual size of MFT entry |

| 0x1c | 4 | Allocated size of MFT entry |

| 0x20 | 8 | Reference to the base FILE record |

| 0x28 | 2 | Next attribute ID |

| 0x2a | 2 | - |

| 0x2c | 4 | MFT record number |

| 0x30 | Varies | Attributes and fix-up values |

Typically, each record is 1,024 bytes long, i.e., two sectors. With the above knowledge, it becomes apparent that there is a significant overlap in keystream bytes for all records. The following figure shows the overlap:

| Record/Index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | <…> |

| 0 | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | |

| 1 | C | D | E | F | G | |||

| 2 | E | F | G | |||||

| <…> |

While the first keystream bytes have only a very few overlapping samples, the situation changes for records with a larger index, and more overlapping samples can be collected. Toward the end of the MFT, the earlier records fade out and the remaining records accumulate again to relatively few samples. Two different approaches were evaluated to exploit the keystream reuse:

MFT Header, where it is assumed that the first few bytes of the MFT header are constant; and

Byte histogram, where the probability is calculated that a plaintext byte occurs for a given sector.

The idea is to iterate over the MFT and emulate the sector progression of the NotPetya/Petya implementation. For each MFT record, the potential keystream bytes in a data structure are collected. If the same keystream byte is found, the respective certainty is updated. After the MFT has been parsed, the data structure is analyzed and only the candidates that meet certain conditions are set as keystream bytes.

MFT Header Attack

In the overwhelming majority of records, the first eight bytes are 46 49 4C 45 30 00 03 00. Under this assumption, the keystream can be directly derived. However, as only the first eight bytes of the plaintext can be recovered, this attack cannot decrypt records toward the end of the MFT. Moreover, at most, four samples can be collected for each keystream index. Therefore, we refined this method to allow for a wider range of possible bytes, called byte histogram.

Byte Histogram Attack

The fact that most elements in the MFT record have a fixed size can be exploited. From this fact it follows that the same data types appear at the same offset within each record. To get a ground truth about the presence of a byte at a given offset, the histogram for each offset in the MFT record was calculated over a set of 1.1 million records collected from various, real-world Windows installations. Only histograms that have at most 10 different values or that are significantly biased towards a certain value were selected. With this approach more potential keystream samples can be collected from each MFT record.

Evaluation

The approach was evaluated on a Windows XP analysis VM. The VM was infected with NotPetya and a snapshot taken of the infected, but not yet encrypted system. The MFT was extracted and then the VM started to let NotPetya do its work. After that, the encrypted MFT was extracted as well. The clean MFT contained 27,984 records.

Decryption of the MFT

We applied both attacks to the encrypted MFT and compared it with the ground truth. The following results were achieved:

| Attack | Keystream bytes | Recovered records | |

| Correct | Wrong | ||

| MFT Header | 55,914 | 0 | 27,452

(98.10%) |

| Byte Histo | 56,945 | 0 | 27,975

(99.97%) |

While the MFT Header approach could correctly recover about 56,000 keystream bytes, the byte histo method could recover almost 56,000 bytes. Both attacks have zero errors, which is good news for the forensic analysis of the MFT, as the resulting data is very reliable. Regarding the decryption of the MFT, 532 records could not be decrypted with the MFT Header method, and only 9 records could not be decrypted with the byte histo method! Additionally, the certainty at each location was recorded and showed significant differences, as the following excerpt shows:

| Attack | Keystream Index 0 | Keystream Index 100 | ||||

| Plaintext | Key | Certainty | Plaintext | Key | Certainty | |

| MFT Header | 0x46 | 32 | 1.0000 | 0x46 | 80 | 4.0 |

| Byte Histo | 0x46 | 32 | 0.9996 | 0x46 0x94 0x44 | 80 130 82 | 31.1976 1.7088 1.0428 |

The results clearly indicate that the byte histo approach can collect more potential plaintext samples per keystream index and thus add up to more confidence in the resulting keystream. When a location cannot be solved, the byte histo approach can show more fine-grained alternative suggestions for the semi-automated recovery of MFT records.

Conclusion and Outlook

The decryption of computers encrypted with NotPetya/Petya is a challenging task. In this blog post, we showed that it is possible to decrypt the MFT, which is a precondition to decrypting the whole disk. In the future, we aim to decrypt the complete file system, a task with its own challenges. <1> For a list of suitable live CDs, see http://wiki.sleuthkit.org/index.php?title=Tools_Using_TSK_or_Autopsy <2> https://github.com/alexwebr/salsa20

![Helping Non-Security Stakeholders Understand ATT&CK in 10 Minutes or Less [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/video-ATTCK2-1?wid=530&hei=349&fmt=png-alpha&qlt=95,0&resMode=sharp2&op_usm=3.0,0.3,2,0)

![Qatar’s Commercial Bank Chooses CrowdStrike Falcon®: A Partnership Based on Trust [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/Edward-Gonam-Qatar-Blog2-1?wid=530&hei=349&fmt=png-alpha&qlt=95,0&resMode=sharp2&op_usm=3.0,0.3,2,0)