As demonstrated in the previous blog post about decryption of Petya/NotPetya, almost the complete Master File Table (MFT) can be decrypted. In this post, we describe our approach to collect more keystream bytes, which eventually leads to decrypt the complete disk.

Technical Analysis

Encryption of Files

MFT records already store the content of a file, if the file is at most 900 bytes in size. This means that the tool decryptPetya.py from our first blog post can already decrypt these files. However, many critical

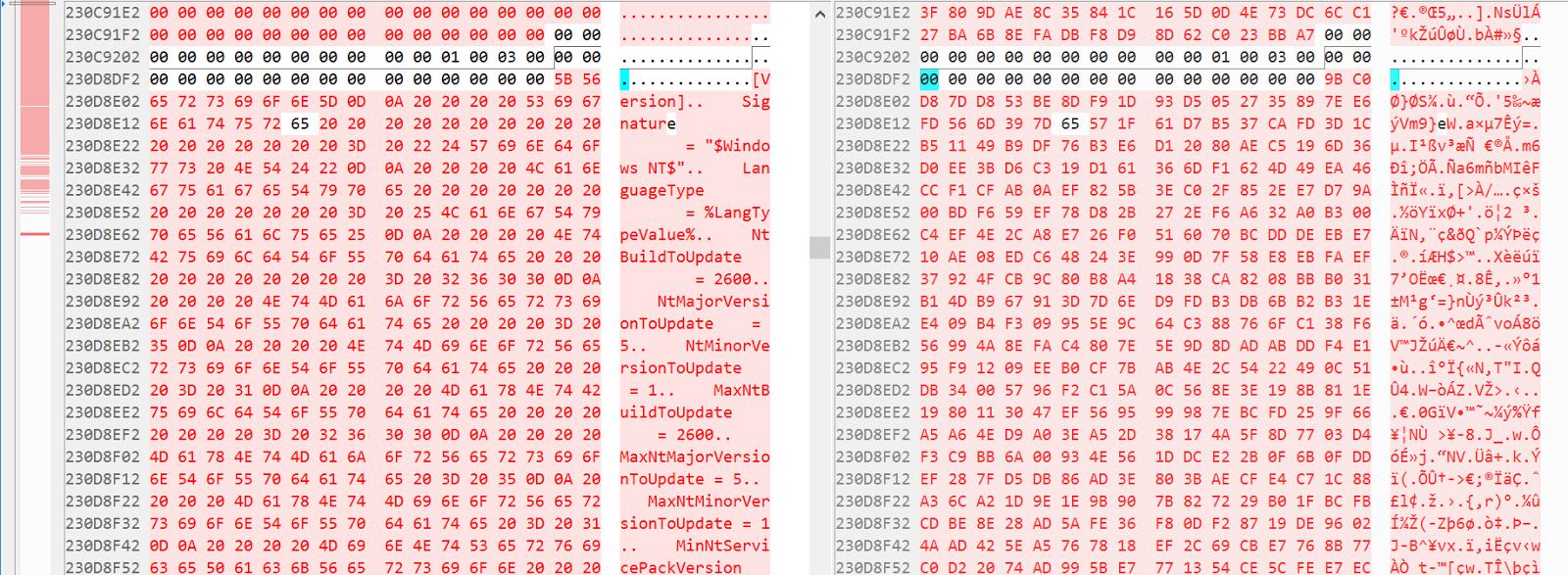

files stored on disk are larger than 900 bytes. When the file size exceeds 900 bytes, the MFT record points to the respective cluster on the drive. Petya/NotPetya encrypts the first two sectors of the file content, i.e., the first 1,024 bytes. To get an overview of how files are encrypted on the hard drive, we compared our evaluation disk before and after encryption, side-by-side. The figure below shows the unencrypted disk on the left and the encrypted version on the right). The indicator on the left gives an overview of how the encryption process affects a wide area of the hard drive. This means that much of the keystream material is used and needs to be recovered for a complete decryption of the hard drive.

Figure 1. NotPetya disk layout before and after encryption

Figure 1. NotPetya disk layout before and after encryption

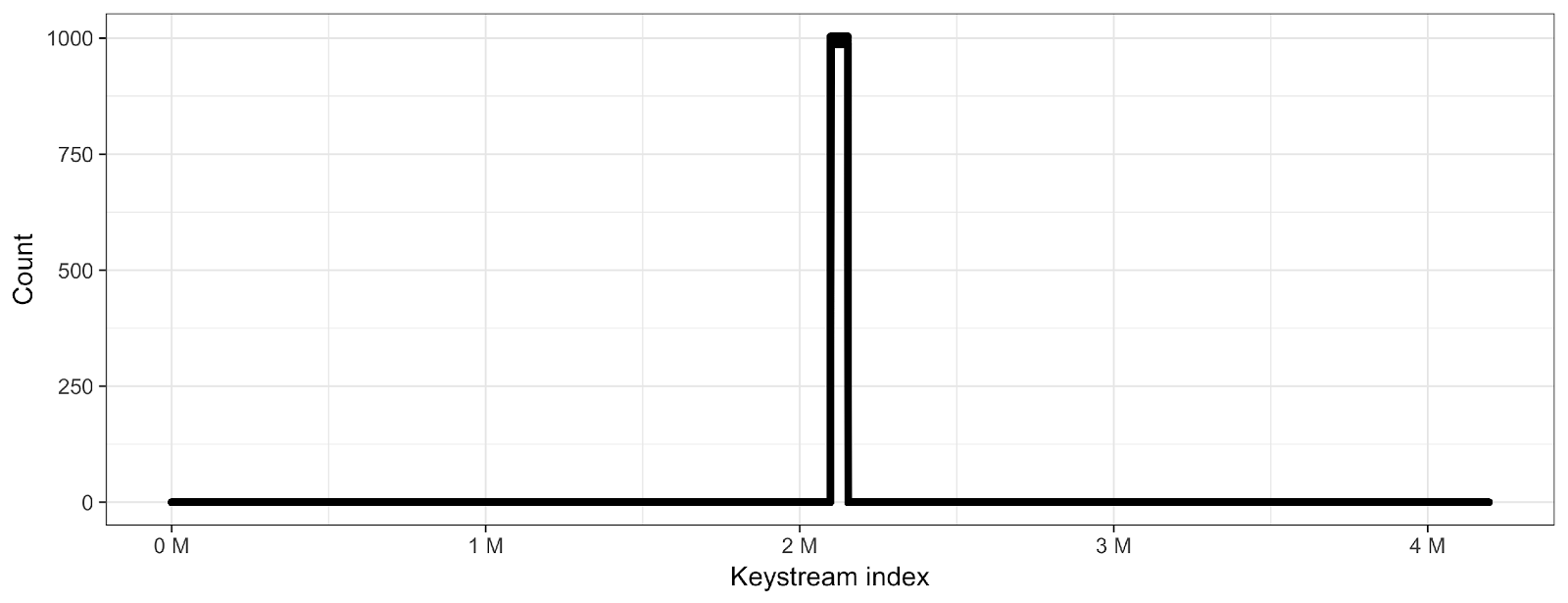

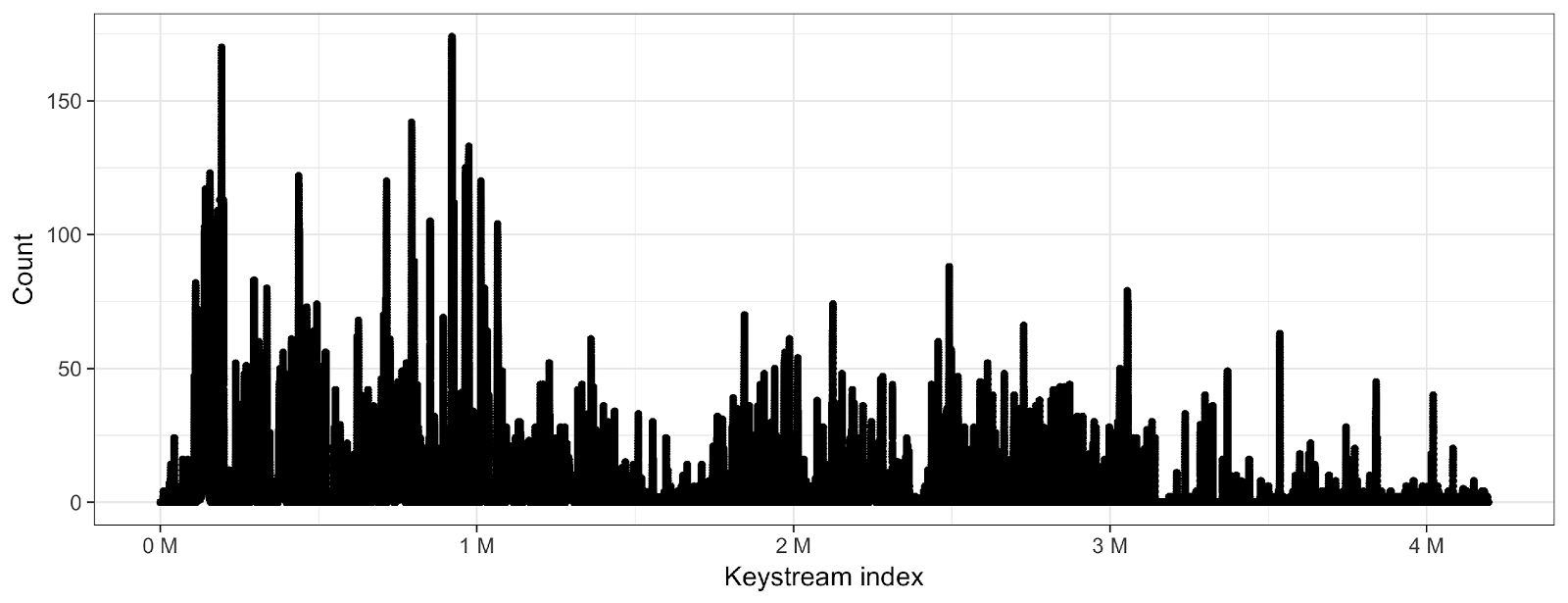

To get a better overview of the decryption potential, we counted the number of encrypted bytes on the hard disk with regard to their location in the keystream. If the number of data points for a given keystream index is high, the probability that the keystream at this index can be decrypted is similarly high. In the previous blog post we already pointed out that the keystream length is only 4MB, and hence, it wraps for every 2GB progressions on the hard disk. Below, two plots are shown that count the number of encrypted bytes for a given keystream index. The first one shows the encrypted bytes of the MFT, the second plot shows the encrypted files on the encrypted partition.

While the count per keystream byte is quite high for almost any given MFT record byte, the number is significantly lower for encrypted files. Encrypted files are relatively sparse for three reasons:

While the count per keystream byte is quite high for almost any given MFT record byte, the number is significantly lower for encrypted files. Encrypted files are relatively sparse for three reasons:

- Files are aligned to clusters, which usually comprise 8 sectors

- Files can become quite large and span multiple clusters

- Only the first 1,024 bytes of a file are encrypted

Non-Uniformity of Files

Moreover, files are not as uniformly structured as MFT records, and thus, the plaintext of a given file cannot be guessed as easily. Worse, the NotPetya main component already encrypts a list of file types before shutting down the system. This leads to some file types potentially being encrypted a second time by the boot loader code of NotPetya. For more details, see our previous technical analysis.

Random Distribution

Additionally, encrypted files are distributed more or less randomly over the keystream. Hence, sometimes only very few sample bytes, if any, are available for keystream recovery analysis. For example, the keystream area between 3MB and 4MB of our test hard drive is very sparsely populated.

Decryption Approaches

The central idea to decrypt systems infected with Petya/NotPetya is to exploit the crypto flaws that were

described in our previous blog, namely:

- Many-times pad, i.e., heavy re-use of keystream material

- Short keystream periodicity of only 4MB

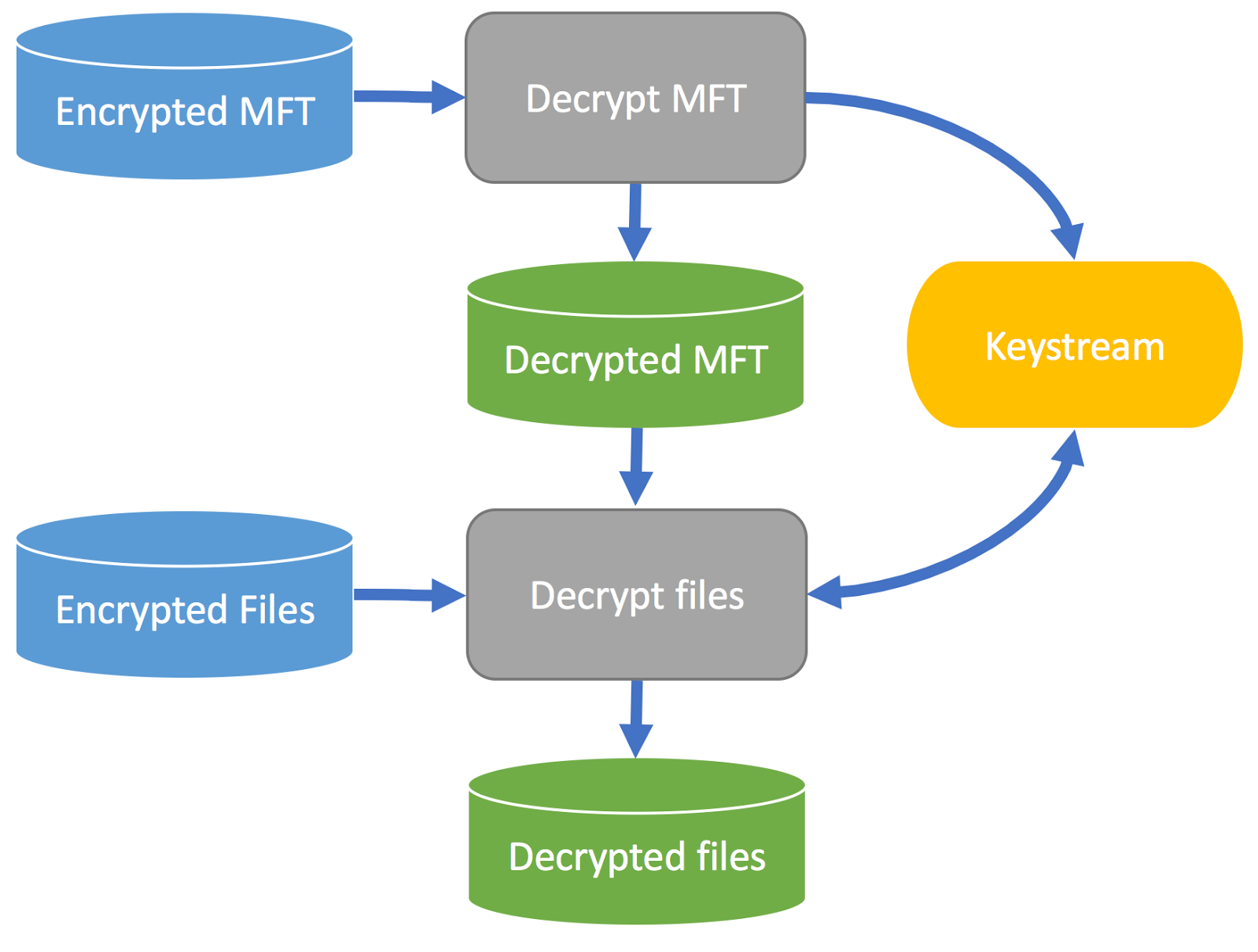

As with the decryption of the MFT, exploiting these flaws relies on gathering as much potential plaintext as possible. With its help, the keystream can hopefully be rebuilt and consecutively, files of interest can be decrypted. The plan can be drafted as follows:  First, decrypt the encrypted MFT. This results in parts of the keystream and the decrypted MFT. Next, parse the decrypted MFT to collect potentially known plaintext of encrypted files. This results in more potential keystream bytes. With their aid, rebuild the keystream and finally decrypt the encrypted files. Still, the problem of not knowing the underlying plaintext needs to be solved. Three approaches are possible to tackle the problem of uncertain plaintext:

First, decrypt the encrypted MFT. This results in parts of the keystream and the decrypted MFT. Next, parse the decrypted MFT to collect potentially known plaintext of encrypted files. This results in more potential keystream bytes. With their aid, rebuild the keystream and finally decrypt the encrypted files. Still, the problem of not knowing the underlying plaintext needs to be solved. Three approaches are possible to tackle the problem of uncertain plaintext:

- For structured files: Accumulate the location-aware histogram for given file types (Location Histogram)

- For unstructured files: Guess the overall probability of a byte for a given file type (General Histogram)

- For known files: Make use of metadata in the MFT record to guess the plaintext (Known Files)

In the following, we describe the approaches in detail.

Location Histogram

Some file types have a well-defined structure. For example, Windows registry files have a fixed header structure.

General Histogram

Even when files are unstructured, they still might yield some plaintext bytes. Here, we use the idea that certain file types prefer some bytes over others. For example, many executable formats, such as PE files, contain lots of null bytes, or plaintext files, such as source code, that contain many blanks.

Known Files

But what about all those well-known files, such as Windows system files? Each MFT record stores, amongst other data, the file name and its size. This metadata can be used to search for the original file. If the file is common enough, chances are high that the file is indexed somewhere. Sources to find these files include:

- Default installations of Windows

- Installed programs

- Databases of binaries, e.g., VirusTotal

The idea here is to create a database of known files or search binary databases online. If a file was found, retrieve it and compare it to the carved file from the encrypted disk – sans the first 1,024 bytes. If both files are identical, chances are good that the first kilobyte is equal as well, so the respective keystream can be recovered with high confidence.

Creation of a “Ground Truth”

The crux of all approaches is to have a preferably unbiased ground truth. To that end, we collected 11 different Windows installations ranging from Windows XP to Windows 10, 32 and 64 bits. This resulted in almost 340,000 unique files. On this basis, we calculated the histograms described above and gathered the known files.

Results: Test Disk

We added 1,000 test files, accumulating to 2.3GB, to a Windows XP VM and let NotPetya encrypt the hard drive. We then executed the file recovery and recorded the proportion of the different plaintext recovery methods. Overall, almost 50 percent of the keystream could be derived. As almost all of the encrypted files are located inside that keystream area, 99.5 percent of the encrypted test files could be successfully recovered.

| Attack | Keystream bytes | Recovered Files | ||

| Correct | Wrong | |||

| General Histogram | 0.31% | 0.00% | (82) | 2 |

| Location Histogram | 4.50% | 0.00% | (122) | 81 |

| Known Files | 43.19% | 0.08% | 912 | |

| Combined | 48.01% | 0.08% | 995 | |

Results in the Real World

As nice as synthetic data is for verifying an approach, the problem remains that it might bear only a remote resemblance to reality. However, we had the opportunity to analyze a couple of hard drives which had been encrypted by NotPetya in the wild. In all but one of these cases, we could recover between 74 percent and 98 percent of the keystream. With it, we could successfully decrypt almost all of the encrypted files. Note that in this case, we could only verify the integrity of the decrypted files by manual inspection, as we had no ground truth. In one case, the MFT could not be extracted, as the corresponding MFT record had been encrypted by NotPetya, probably due to a programming error. Note that it still is possible to extract the MFT manually, just not automatically using the tools discussed in our previous blog post.

Conclusion

Recovering hard disks encrypted by Petya/NotPetya is a tedious, yet possible task. A combination of three different known plaintext attacks resulted in a file recovery of almost all files on a synthetic test disk. Real-world cases support the efficacy of our approach. We decided to not release the tool to the general public yet, as

manual interaction is still often necessary. We plan to do so once we have analyzed more encrypted disks and feel confident that the tool can be run without much interaction. If you have been infected with Petya or NotPetya, please contact us. We may be able to help you!

For more information on stopping ransomware attacks using the CrowdStrike Falcon® platform, please visit this page. Watch the CrowdCast presentation, “Is Ransomware Morphing Beyond The Ability of Standard Approaches to Stop It?”

![Helping Non-Security Stakeholders Understand ATT&CK in 10 Minutes or Less [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/video-ATTCK2-1?wid=530&hei=349&fmt=png-alpha&qlt=95,0&resMode=sharp2&op_usm=3.0,0.3,2,0)

![Qatar’s Commercial Bank Chooses CrowdStrike Falcon®: A Partnership Based on Trust [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/Edward-Gonam-Qatar-Blog2-1?wid=530&hei=349&fmt=png-alpha&qlt=95,0&resMode=sharp2&op_usm=3.0,0.3,2,0)