GuLoader, a malware family that emerged in the wild late last year, is written in Visual Basic 6 (VB6), which is just a wrapper for a core payload that is implemented as a shellcode. It is distributed via spam email campaigns with archived attachments that contain the malware. The majority of malware downloaded by GuLoader is commodity malware, with AgentTesla, FormBook and NanoCore being the most predominant.

This downloader typically stores its encrypted payloads on Google Drive. CrowdStrike has observed that GuLoader downloads its payloads from Microsoft OneDrive and also from compromised or attacker-controlled websites. By utilizing legitimate file-sharing websites, GuLoader can evade network-based detection, as these services are not generally filtered or inspected in corporate environments. In addition, the downloaded payloads are encrypted with a hard-coded XOR key embedded in the malware, making it difficult for file-sharing service providers to identify the payload as malicious. GuLoader is an advanced downloader that uses shellcode wrapped in a VB6 executable that changes in each campaign to evade antivirus (AV) detections. The shellcode itself is encrypted and later heavily obfuscated, making static analysis difficult. In this blog, we cover GuLoader’s internal details, including its main shellcode, anti-analysis techniques and final payload delivery mechanism.

Analysis

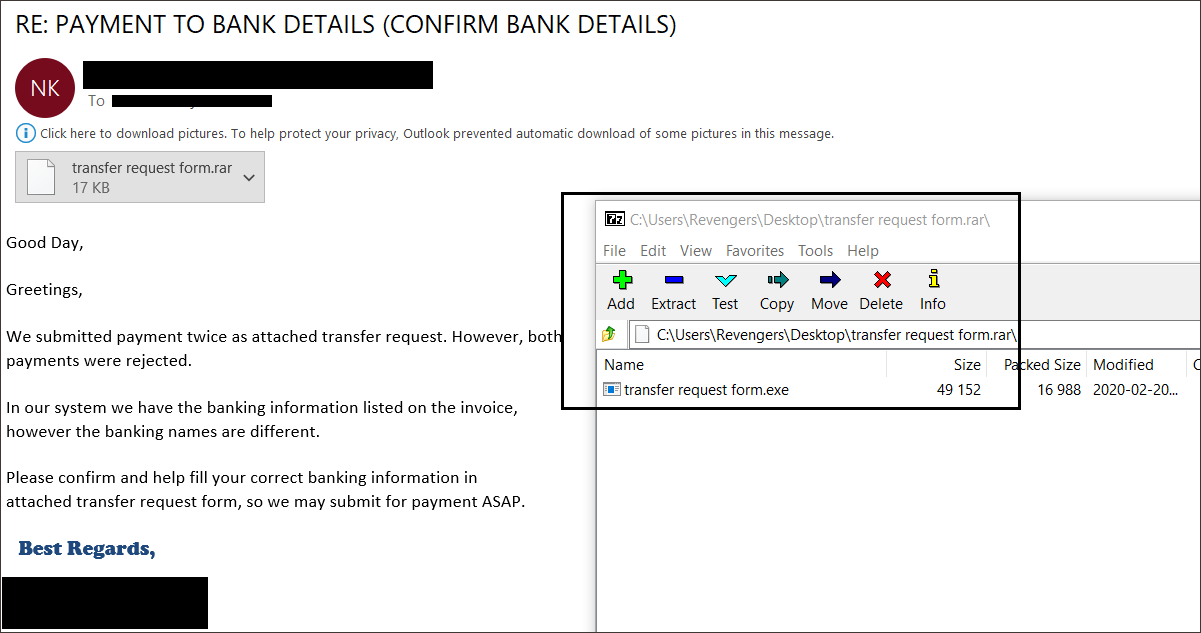

GuLoader is often distributed through spam campaigns that contain the malware embedded in archived attachments. An example of GuLoader spam email is shown in Figure 1.

The attachment contains a malicious executable file named transfer request form.exe. The sample is a PE32 file written in Microsoft Visual Basic (just a wrapper for a shellcode that implements the main functionality), as shown in Figure 2. Strings present inside the sample don’t reveal much as the binary is packed. The sample contains numerous calls to meaningless VB functions that can slow down the analysis. By stepping through the assembly code, we will land into some block of code that is eventually used to decrypt the main shellcode, as shown in Figure 2.

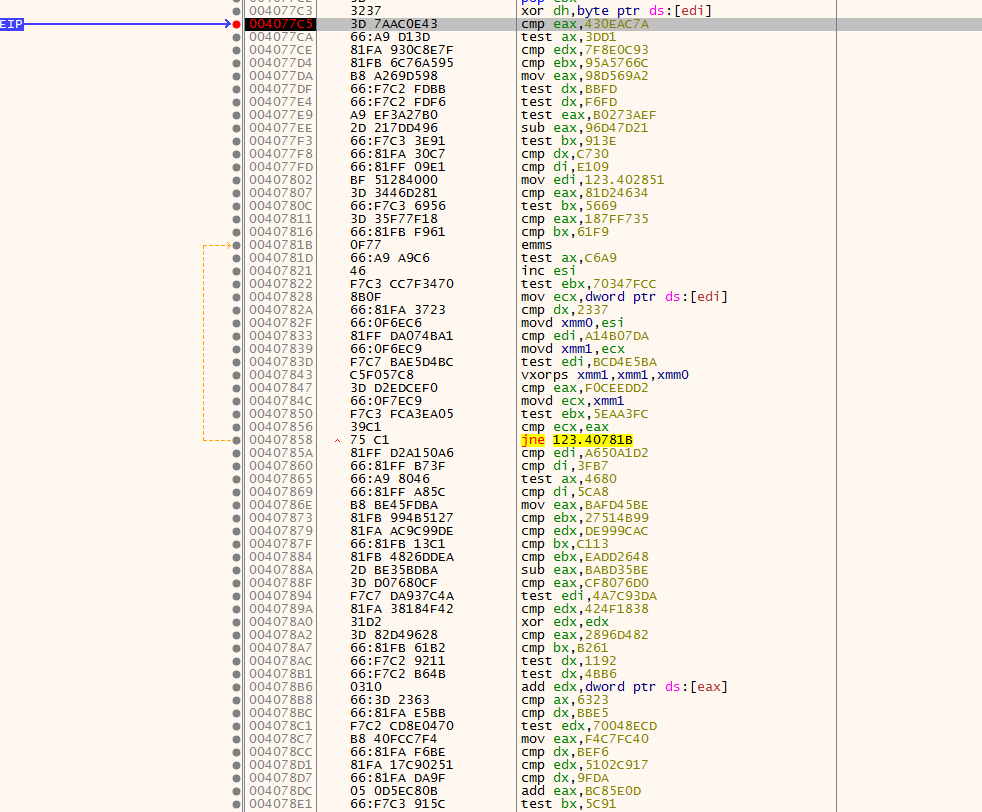

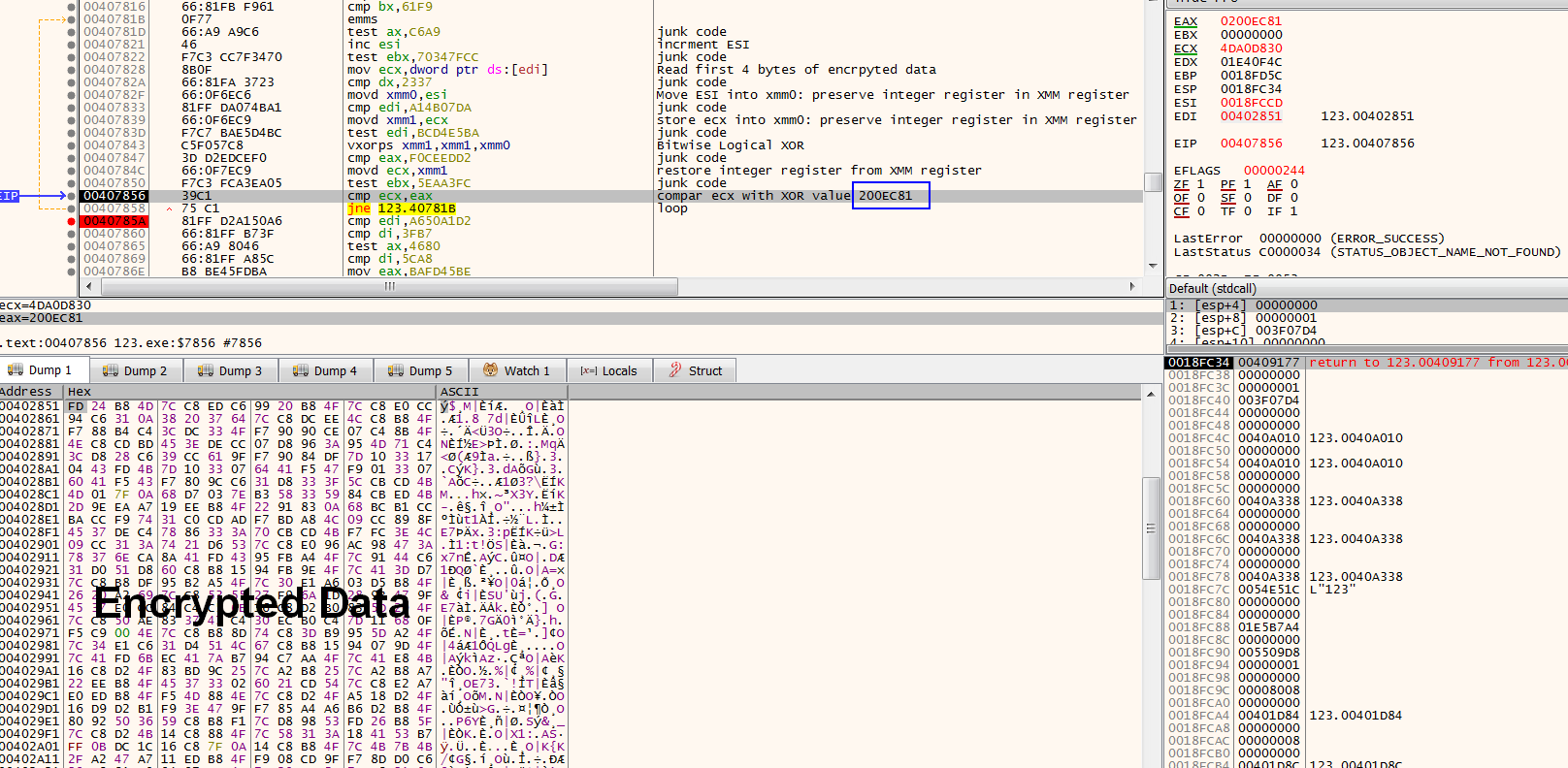

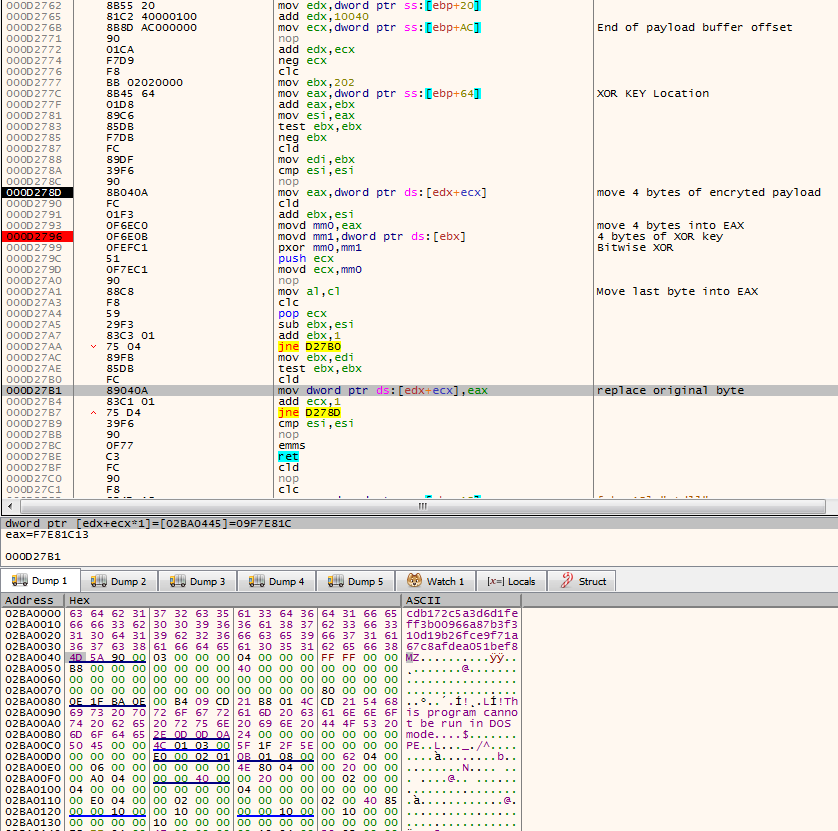

The snippet above contains junk code inserted within legitimate instructions to thwart analysis. After analyzing and understanding this code further, we see that this code is responsible for decrypting the main shellcode in memory. It uses a 4-byte XOR key to decrypt the packed code to extract the final shellcode. The sample takes the first 4 bytes of encrypted data, XORs it with the ESI register and compares it with the value 0x200EC81, as shown in Figure 3.

If it does not match, it keeps incrementing ESI and performs an XOR operation until the result matches the expected value. The value 0x200EC81, read as little-endian, translates into the instruction sub esp, 0x200, which is the actual start of the final shellcode.

(First 4 bytes of encrypted data in little endian

XOR

0x200EC81)

=

XOR Key which for this sample becomes: (0x4DB824FD

XOR

0x200EC81)

=

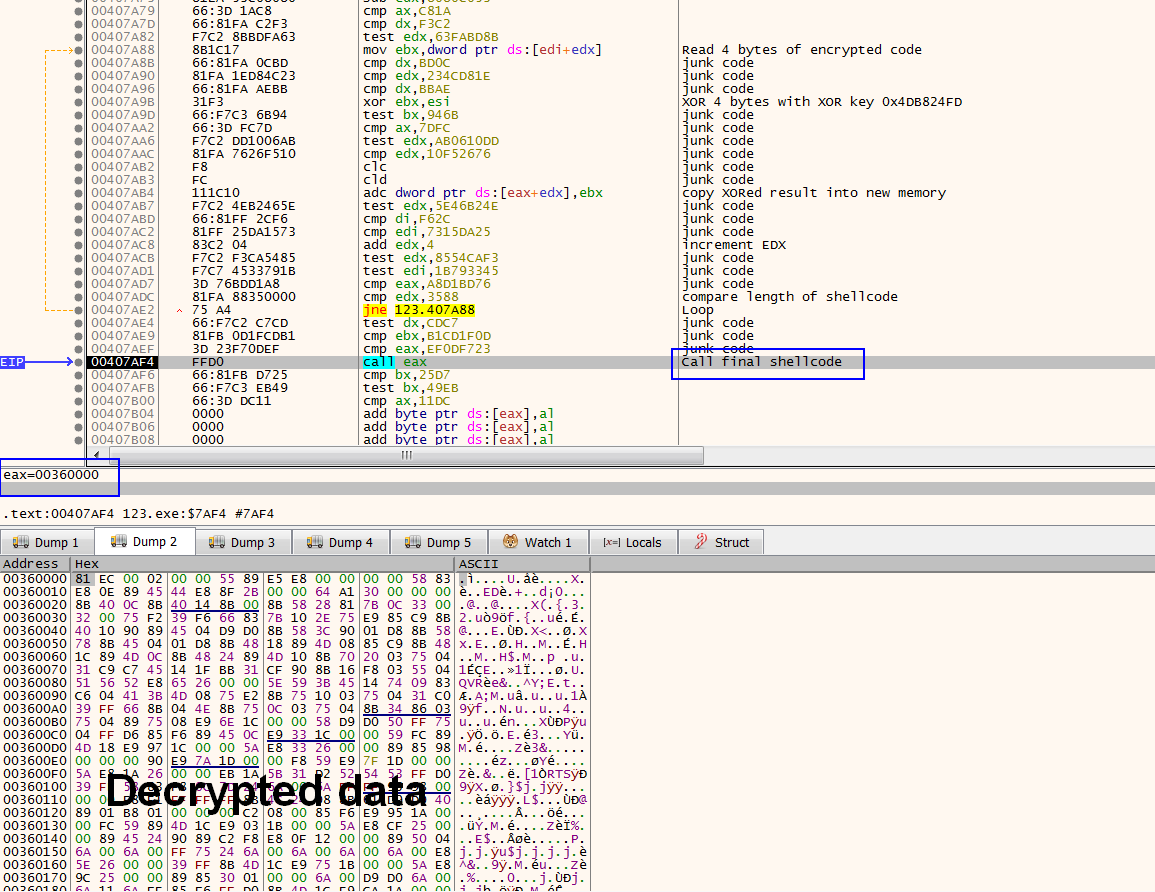

0x4FB8C87C After this, the decryption routine will call VirtualAlloc() to allocate memory and start decrypting the final shellcode into the newly allocated memory by XORing encrypted data with key 0x4FB8C87C, as shown in Figure 4.

Once the shellcode is decrypted, the code will jump into that new shellcode for further execution. Since the decryption routine has decrypted our shellcode, a memory dump of that newly allocated region gives us lots of interesting strings, including API names and the final encrypted payload hosted on Google Drive, as shown below.

ASCII Strings

00001A7F

hxxps<:>//drive.google.com/uc?export=download&id=1THD-itP7iOm05w_6SQSb-C3tgd3cLMzO 00001ADE

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; Trident/7.0; rv:11.0) like Gecko 0001B28

wininet.dll 00001B3B

InternetOpenA 00001B4E

InternetSetOptionA 00001B68

InternetOpenUrlA 00001B7E

InternetReadFile 00001B94

InternetCloseHandle 00001BCB

ntdll 00001BD6

NtCreateSection 00001BEB

NtMapViewOfSection 00001C03

NtClose 00001C10

NtGetContextThread 00001C29

NtSetContextThread 00001C43

NtProtectVirtualMemory 00001C5F

NtAllocateVirtualMemory 00001C7C

NtWriteVirtualMemory 00001C98

NtOpenFile 00001CA9

NtResumeThread 00001CBD

DbgBreakPoint 00001CD0

DbgUiRemoteBreakin 00001CE8

NtSetInformationThread 00001D05

kernel32 00001D13

WaitForSingleObject 00001D2D

LoadLibraryA 00001D40

CreateProcessInternalW 00001D5C

GetLongPathNameW 00001D73

TerminateProcess 00001D8A

CreateThread 00001D9C

AddVectoredExceptionHandler 00001DBD

TerminateThread 00001DD2

CreateFileW 00001DE5

WriteFile 00001DF5

GetFileSize 00001E07

ReadFile 00001E15

CloseHandle 00001E26

Sleep 00001E31

advapi32 00001E3F

RegCreateKeyExA 00001E54

RegSetValueExA 00001E68

user32 00001E74

EnumWindows 0000210F

Startup key 00002120

Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce 000021A0

shell32 000021AD

SHCreateDirectoryExW 000021C8

ShellExecuteW

Analyzing Shellcode

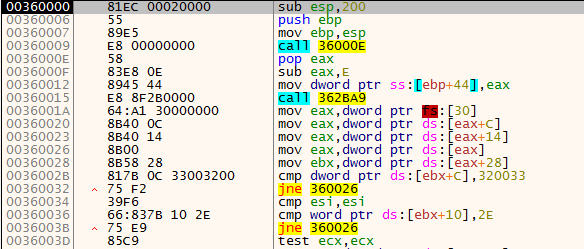

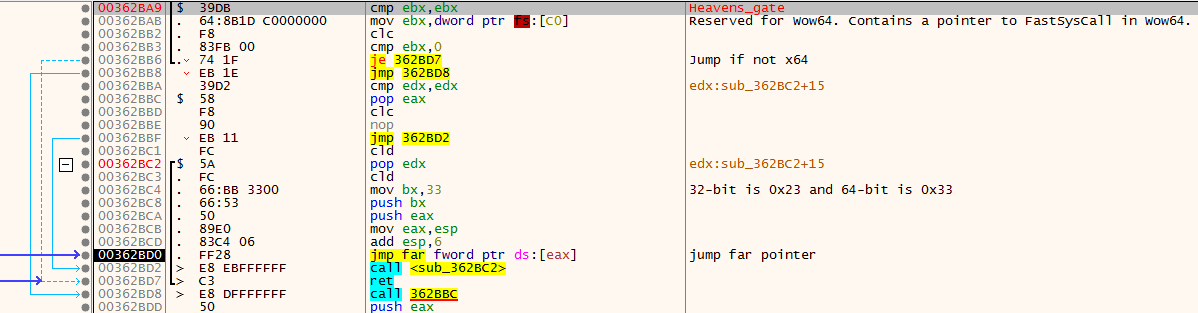

This entire shellcode is heavily obfuscated, contains lots of junk code and also contains anti-analysis and anti-debugging tricks to make shellcode analysis more difficult. The shellcode starts with a few lines that prepare the stack and registers for use within the function before an interesting call 362BA9 instruction, as shown in Figure 6.

The code in Figure 6 applies the Heaven's Gate technique, the technique for executing code from x86 to x64 with the far JMP command. The code checks the FS:<0xC0> register value to see whether the system is x64 or not. If it is x64, the shellcode uses the Heaven's Gate call technique.

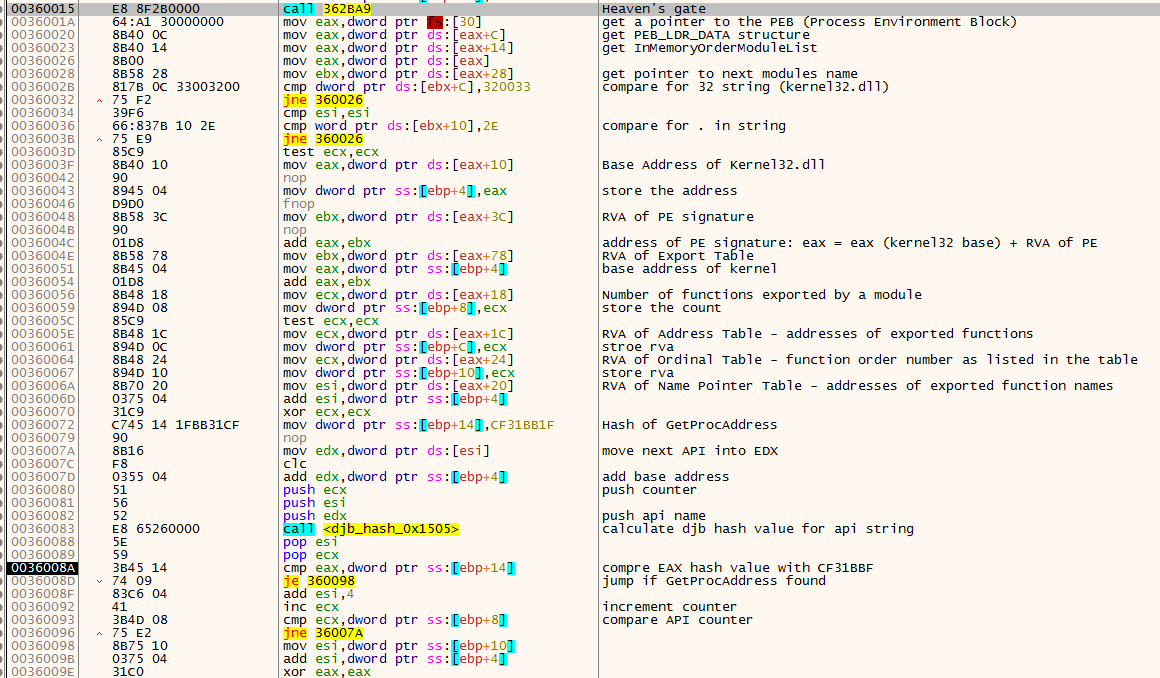

Accessing Kernel Imports via PEB

When a malware injects a payload into memory, it needs to determine which API calls to use; this is done by using the Process Environment Block (PEB), which is always located at offset 0x30 within the Threat Information Block (TIB), which in turn is referenced by the segment register FS:<0x00>. For example, a common method is to find the kernel32.dll address from the loaded modules and enumerate the export table of kernel32.dll to find GetProcAddress() and start loading the API addresses required for its operation. Figure 7 shows the code that does this after the Heaven’s Gate function call.

DJB2 Hashes for Windows API Resolution

When GuLoader needs to call a Windows API function, it must first resolve the function’s address, as it does not have an Import Address Table (IAT). The code shown in Figure 7 iterates through export functions of kernel32.dll one by one, calculates the DJB2 hashes for each export API and compares those with the hardcoded hash value CF31BB1F (DJB2 hash of GetProcAddress API).

Python Snippet for DJB2 Hash Calculation

val = 0x1505inString = "GetProcAddress"for ch in inString:

val += (val << 5)

val &= 0xFFFFFFFF

val += ord(ch)

val &= 0xFFFFFFFFprint(hex(val).upper().lstrip("0X").rstrip("L"))

Once the shellcode matches the hash for the string name GetProcAddress, it will calculate its API address from kernel32.dll. Then it will start resolving the required APIs shown in the appendix at the end of this blog.

Anti-Sandbox/Anti-Emulation

GuLoader also checks the number of application windows to detect an analysis environment. This check uses the function EnumWindows to enumerate and count all top-level windows on the screen. If the number of windows is less than 12, the malware calls TerminateProcess with its own process handle as the parameter to terminate. This might have been done to evade sandboxes or emulator environments.

Anti-Attach: Patching DbgBreakPoint and DbgUIRemoteBreakin

The Windows API functions DbgBreakPoint and DbgUiRemoteBreakin are called when a debugger attaches to a running process. The shellcode patches these two APIs by replacing the INT3 opcode of DbgBreakPoint with opcode 90 (NOP, or “no-operation,”

to do nothing), and replacing the first few bytes of DbgUIRemoteBreakin with a dummy call (to cause a crash). This is done to prevent a debugger from attaching to the process, as shown in Figure 8.

Unhooking API Hooks

The shellcode performs some pattern matching in the NTDLL API’s code functions — for example, searching for the byte pattern “\xb8\x00.{3}\xb9,” which represents NTDLL calls to system calls. Many security products like AV, endpoint detection and response (EDR) and sandbox software put their hooks here, so they can detour the execution flow into their engines to monitor and intercept API calls and block anything suspicious. Basic user-mode API hooks by AV/EDR are often created by modifying the first 5 bytes of the API call with a jump (JMP) instruction to another memory address pointing to the security software. Considering this hooking mechanism, the shellcode scans for all such system calls and then restores its first 5 bytes to the original bytes in NTDLL, as shown in Figure 9.

As a result, GuLoader bypasses any hooks installed by anti-malware software. Lastly, it resets the NTDLL’s memory permissions back to PAGE_EXECUTE_READ only.

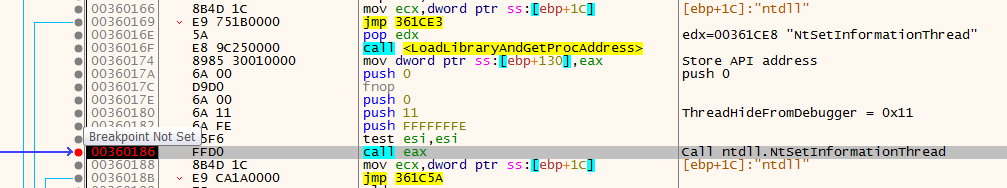

Anti-debug (NtSetInformationThread)

Next, the shellcode calls the NtSetInformationThread function with ThreadHideFromDebugger (0x11) as the second parameter for hiding the thread from a debugger, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10:

Figure 10: NtSetInformation thread function with ThreadHideFromDebugger parameter (click image to enlarge)This causes a crash in the debugged application when a breakpoint is hit in the hidden thread or when the debugger steps through the instructions.

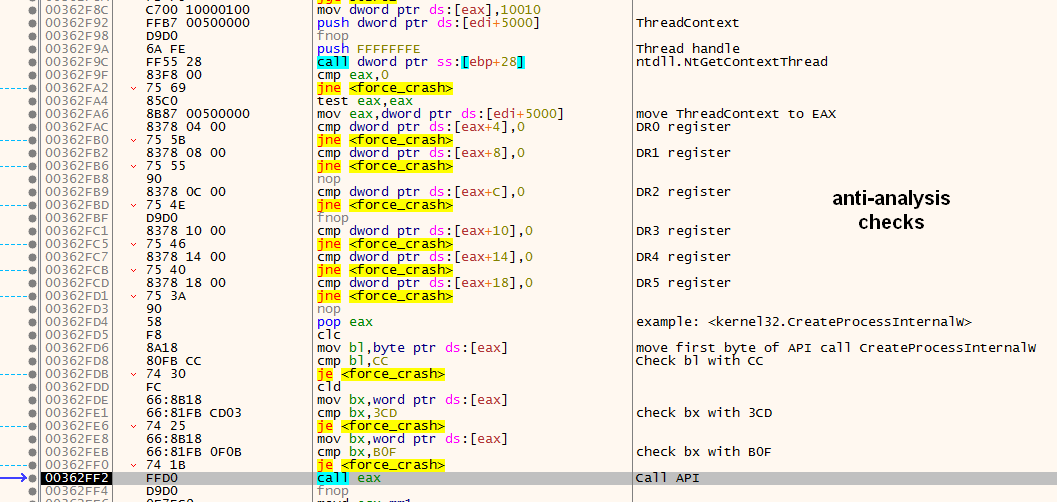

Anti-Analysis/Debug Techniques

The shellcode uses several anti-debugging techniques. The shellcode detects if hardware breakpoints or software breakpoints have been set, each time it calls several key API functions, as shown in Figure 11.

During their malware analysis, analysts often use hardware or software breakpoints at the beginning of suspicious API calls — for example, by patching the first byte of CreateProcessInternalW with 0xCC.

By calling the NtGetContextThread function, debug registers (DR0 through DR7) can be used to detect hardware breakpoints, while 0xCC, 0X3CD and 0xB0F opcodes are used to detect software breakpoints (if present) at the beginning of the API calls.

Process Hollowing Injection

Process hollowing is a code injection technique used by malware in which the executable code of a legitimate process in memory is replaced with malicious code. By executing within the context of legitimate processes, the malware can bypass security solutions. The shellcode similarly uses process hollowing techniques in order to inject its code into the legitimate process (here RegAsm.exe or MSBuild.exe or RegSvcs.exe) with a slight variation. Here, shellcode doesn’t unmap memory code of legitimate processes; instead it uses the NtCreateSection API section object to inject its malicious code. The process is as follows: 1) Calls kernel32.CreateProcessInternalW to create the Windows legitimate process "C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v2.0.50727\RegAsm.exe" with CREATE_SUSPENDED(0x00000004) flags. If it doesn’t find RegAsm.exe, it will try to find MSBuild.exe or RegSvcs.exe in the same directory path and loop until it finds one of them. 2) Opens a file handle to the hard-coded file path "C:\Windows\syswow64\mstsc.exe" using ZwOpenFile

3) Calls ntdll.NtCreateSection on the file handle for mstsc.exe. The ZwCreateSection function creates a section object that represents a section of memory that can be shared. This file handle is used to create a new section object with the DesiredAccess parameter. 4) The section is then mapped in the targeted process (RegAsm.exe) using the function ntdll.NtMapViewOfSection with the BaseAddress parameter set to 0x400000. This maps the section in the base address 0x400000, which is typically the address used to map the executable file image of the process.

5) Calls

ntdll.NtWriteVirtualMemory in order to write the shellcode in the newly allocated memory of the targeted process. 6) Calls ntdll.NtGetContextThread to obtain information about the main thread within the suspended subprocess. 7) After the shellcode has been written to the memory of the targeted process, the execution needs to be redirected to it. To achieve this, GuLoader makes use of the function ntdll.NtSetContextThread to change the context of the only thread running in the targeted process (still in a suspended state). This context change sets the EIP register to the address that points to the beginning of the shellcode, which makes the execution start there.8) Calls

ntdll.NtResumeThread to resume the new thread in RegAsm.exe to execute the malicious shellcode.

Final Payload

After GuLoader has successfully injected into the RegAsm.exe

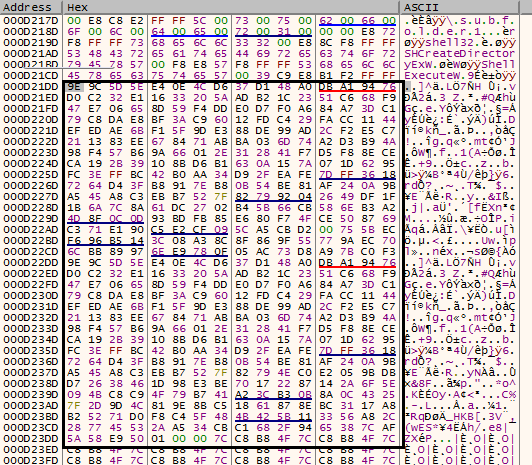

process, its shellcode will download the final payload from the Google Drive link in memory in an encrypted form, as shown in Figure 12.

The real encrypted payload is appended after the first 64 bytes of random data. The GuLoader shellcode uses a hardcoded XOR key with a length of 517 bytes for this sample (as shown in Figure 13) to decrypt the final payload.

The following piece of code from the shellcode decrypts its encrypted payload back into its original one, as shown in Figure 14.

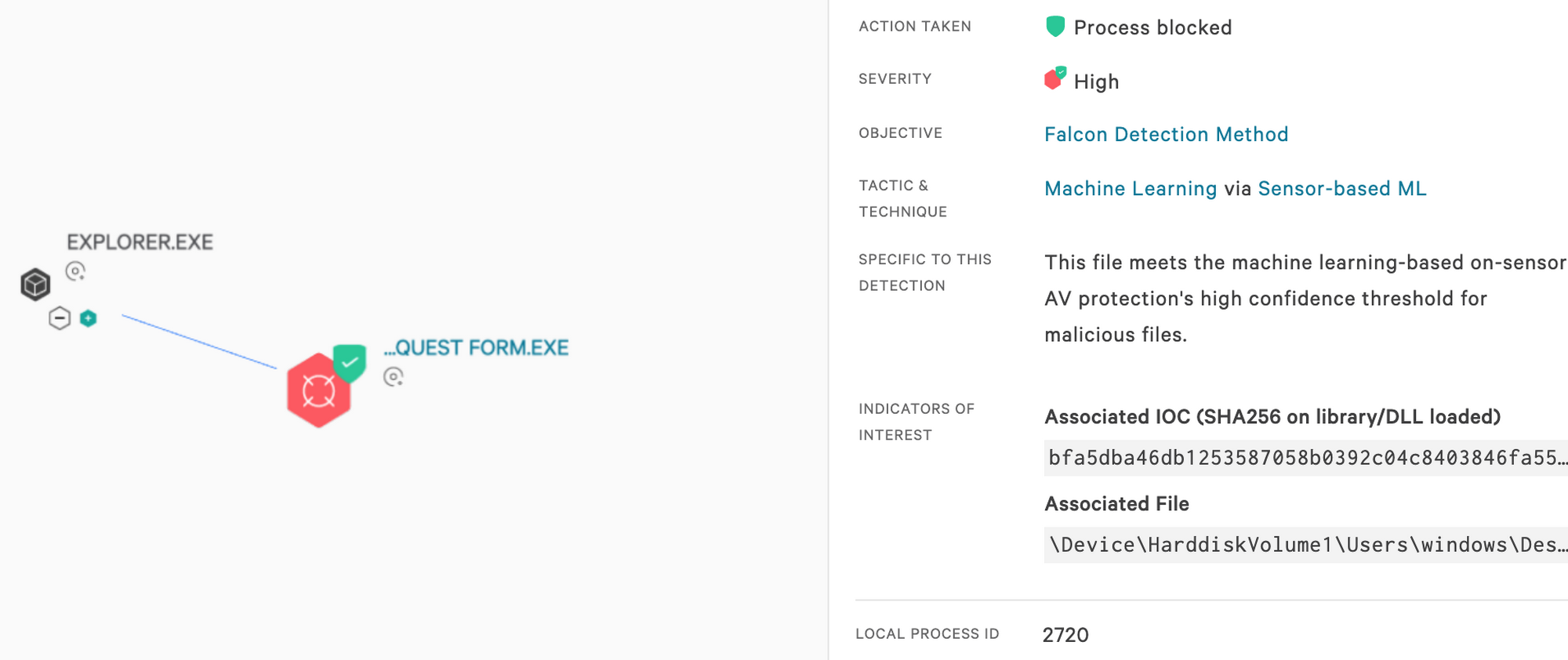

How the CrowdStrike Falcon® Platform Protects Against GuLoader

The CrowdStrike Falcon®® platform has the ability to detect and prevent GuLoader by taking advantage of the behavioral patterns indicated by the malware. By turning on suspicious process blocking, Falcon ensures that GuLoader is killed in the very early stages of execution.

In addition, the CrowdStrike® machine learning (ML) algorithm provides additional coverage against this malware family, as illustrated in Figure 16.

Conclusion

GuLoader has been very active in 2020 and is frequently used by criminals to distribute their malware like AgentTesla, FormBook and NanoCore. The use of process hollowing and hosting encrypted payloads on Google Drive is designed to bypass many security solutions — but it doesn’t bypass CrowdStrike Falcon®.

Appendix: APIs Resolved by GuLoader

- LoadLibraryA

- TerminateProcess

- EnumWindows

- ZwProtectVirtualMemory

- DbgBreakPoint

- DbgUIRemoteBreakin

- NtGetContextThread

- NtSetContextThread

- NtWriteVirtualMemory

- NtCreateSection

- NtMapViewOfSection

- NtOpenFile

- NtClose

- NtResumeThread

- CreateProcessInternalW

- GetLongPathNameW

- Sleep

- CreateThread

- WaitForSingleObject

- TerminateThread

- AddVectoredExceptionHandler

- CreateFileW

- WriteFile

- CloseHandle

- GetFileSize

- ReadFile

- ShellExecuteW

- SHCreateDirectoryExW

- RegCreateKeyExA

- RegSetValueExA

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

| File | SHA256 |

| SPAM Email | 38e6cef6c556cb8ce5254876fd43caf59bbb8239a1ea679891a4d423aafb08dc |

| Email Attachment | c61f1d14582a38474f56426975cc4a2b2fa9ff172c915af9781c9d5682cb629e |

| Guloader Payload

| bfa5dba46db1253587058b0392c04c8403846fa55d7dcf1044e94e6a654d4715 |

Additional Resources

- Learn more about the CrowdStrike Falcon® platform by visiting the product webpage.

- Learn more about CrowdStrike endpoint detection and response by visiting the Falcon Insight™ webpage.

- Test CrowdStrike next-gen AV for yourself. Start your free trial of Falcon Prevent™ today.

![Helping Non-Security Stakeholders Understand ATT&CK in 10 Minutes or Less [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/video-ATTCK2-1)

![Qatar’s Commercial Bank Chooses CrowdStrike Falcon®: A Partnership Based on Trust [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/Edward-Gonam-Qatar-Blog2-1)