Defending an organization from today’s sophisticated attacks is no easy task. It often requires security teams to be ready at a moment’s notice to respond to an incident, in addition to managing the day-to-day responsibilities of securing the organization. To be effective, security teams must have well-defined policies and solid detection capabilities. This dynamic often drives an ongoing arms race between blue teams and red teams, with both seeking increasingly sophisticated tooling and detection capabilities. However, security professionals can often optimize their efforts and gain a strategic advantage by anticipating likely attack paths and taking steps to block attackers from using these paths. This blog focuses on a common security issue frequently observed during red team engagements: hidden administrator accounts. It also introduces a tool originally designed for red teams that now provides blue teams with the ability to detect and remediate this common security issue.

What is a Hidden Administrator Account and Why Do I Care?

Hidden administrator accounts are domain accounts that provide administrator access to sensitive systems like domain controllers, exchange servers or database servers. These accounts may not belong to privileged Active Directory (AD) groups (i.e. Domain Admins), but they still have access to the same systems. The permissions for these accounts are directly assigned using access control lists (ACL) on AD objects. These hidden administrator accounts are often service or maintenance accounts that perform automated, routine tasks in the environment. In addition, hidden administrator accounts often have access to multiple systems in the environment. Of concern is that these accounts don’t typically receive the same attention regarding configuration review or password management and monitoring as administrative accounts belonging to human users. As a result, they present an attractive target for adversaries, who leverage these service accounts for both lateral movement and gaining access to multiple systems. Hidden administrator accounts are also often targeted by self-propagating malware, including those used in ransomware and cryptomining attacks. Exploitation of these administrator privileges allows malware to easily spread throughout an organization.

CrowdStrike Red Team Use Case

CrowdStrike recently performed an adversary emulation penetration test for a client organization that had gone through a large effort to make improvements to its AD structure. This organization restricted its administrator account privileges and segregated administrator and user roles. As is best practice, the client only allowed domain administrator accounts to log onto domain controllers. Additionally, the client implemented logging, monitoring and session management around the use of the domain administrator accounts. Even server administrators were restricted to only accessing the servers for which they had direct responsibility. During the lateral movement and credential dumping phase of the test, we came across two different service accounts. One was a service account that performed storage area network (SAN) maintenance and also had local administrative access to a large portion of the environment. The other one was what we call the “golden key.” It was a service account that had been created to pull security information from all the domain controllers. It was not in the “Domain Administrators” AD group, so it was not monitored and its sessions were not managed. This golden key account had local administrator access to every domain controller in the network, essentially making it a hidden domain administrator account. In another adversary emulation engagement, we moved between domains throughout the environment to compromise two geographic regions of the company. Each domain contained its own domain accounts and was managed by separate IT staff. Once we fully compromised one domain, we began looking for misconfigured domain trusts and instances of service accounts used in both domains. We discovered a service account that was being used for network performance monitoring, which had local administrator access to multiple systems. This account was used in both domains and had the same password in each one — a configuration that made it easy for our red team to jump from one domain to another. This dynamic eventually allowed us to fully compromise a geographically dispersed organization. This is another example of unmonitored “administrative” accounts that have extremely powerful access to the networked environment.

What Can be Done About Hidden Admin Accounts

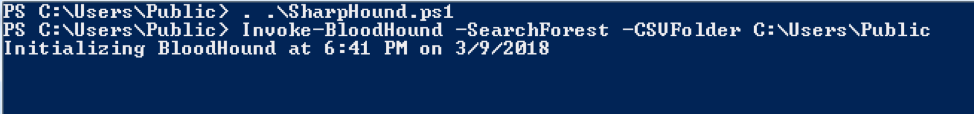

You might be asking, “How does one find these hidden relationships, and how can I make sure this doesn’t happen to my  organization?” One option is BloodHound. No, I’m not talking about the droopy-eyed scent dog — I’m talking about the very popular internal AD reconnaissance tool that many red teams use today. BloodHound is a single page JavaScript web application with a Neo4j database that is fed by a PowerShell script. BloodHound uses graph theory to reveal hidden and often unintended relationships within an AD environment. It was developed by Will Schroeder (@harmjoy), Andrew Robbins (@_wald0), and Rohan Vazarkar (@CptJesus). BloodHound can do in minutes what used to take penetration testers and analysts weeks to develop. Although the tool is very popular in the penetration testing community, we still find some security and IT teams who are not aware of how powerful and beneficial it can be for securing their infrastructure. Specifically, BloodHound can uncover hidden relationships and administrative accounts that would otherwise go unnoticed. To use BloodHound, you must set up the Neo4j community edition database. You will then need to connect the BloodHound web application to the Neo4j database. For full installation instructions, visit the BloodHound Wiki. Once you have set up the database and logged into the BloodHound web application, you need to pull AD data from your environment using the BloodHound PowerShell ingestor. Figure 1 shows a sample command that searches all domains in the forest (-SearchForest) and the folder location used to save the resulting CSV files.

organization?” One option is BloodHound. No, I’m not talking about the droopy-eyed scent dog — I’m talking about the very popular internal AD reconnaissance tool that many red teams use today. BloodHound is a single page JavaScript web application with a Neo4j database that is fed by a PowerShell script. BloodHound uses graph theory to reveal hidden and often unintended relationships within an AD environment. It was developed by Will Schroeder (@harmjoy), Andrew Robbins (@_wald0), and Rohan Vazarkar (@CptJesus). BloodHound can do in minutes what used to take penetration testers and analysts weeks to develop. Although the tool is very popular in the penetration testing community, we still find some security and IT teams who are not aware of how powerful and beneficial it can be for securing their infrastructure. Specifically, BloodHound can uncover hidden relationships and administrative accounts that would otherwise go unnoticed. To use BloodHound, you must set up the Neo4j community edition database. You will then need to connect the BloodHound web application to the Neo4j database. For full installation instructions, visit the BloodHound Wiki. Once you have set up the database and logged into the BloodHound web application, you need to pull AD data from your environment using the BloodHound PowerShell ingestor. Figure 1 shows a sample command that searches all domains in the forest (-SearchForest) and the folder location used to save the resulting CSV files.  Figure 1: Running BloodHound’s PowerShell Ingestor Once the ingestor completes, you will see three CSV files that can be uploaded into BloodHound, as shown in Figure 2:

Figure 1: Running BloodHound’s PowerShell Ingestor Once the ingestor completes, you will see three CSV files that can be uploaded into BloodHound, as shown in Figure 2:

- group_membership.csv

- local_admins.csv

- Sessions.csv

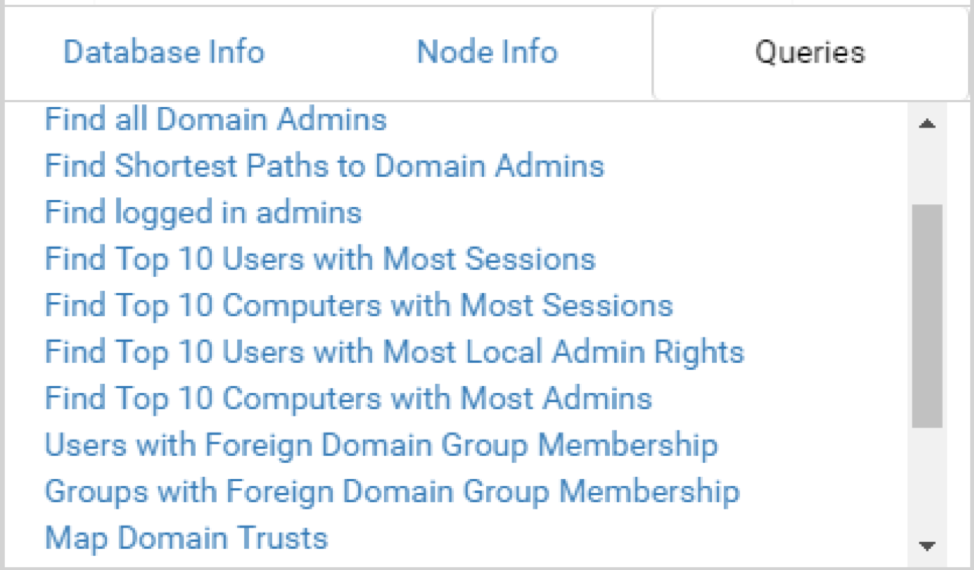

Figure 2: BloodHound Web Application Upload Data After uploading these files, take advantage of the pre-built queries within BloodHound. These queries are a great way to start obtaining important information about your environment. Queries include: viewing all domain administrators; viewing users with the most local administrator rights; or viewing computers with the most administrative user access. One of these queries gives you the ability to map domain trusts, as shown in Figure 3.

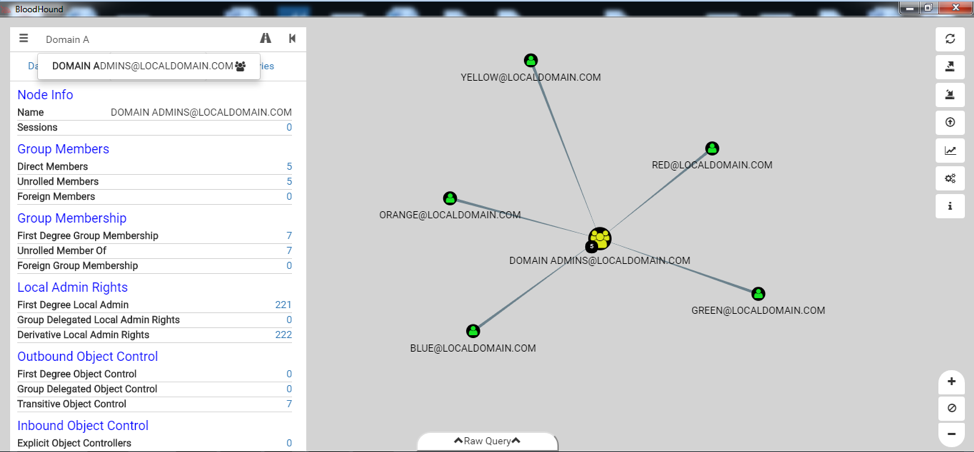

Figure 2: BloodHound Web Application Upload Data After uploading these files, take advantage of the pre-built queries within BloodHound. These queries are a great way to start obtaining important information about your environment. Queries include: viewing all domain administrators; viewing users with the most local administrator rights; or viewing computers with the most administrative user access. One of these queries gives you the ability to map domain trusts, as shown in Figure 3.  Figure 3: BloodHound Pre-Built Analytics Queries When looking for hidden administrator accounts and trust misconfigurations, we will commonly use the pre-built queries “Find Top 10 Users with Most Local Admin Rights” and “Map Domain Trusts.” These queries will provide some quick wins and show you which accounts have access to the most systems, and whether there are two-way trusts between foreign domains that could allow for greater access to the environment. Another great way to find hidden administrator accounts is to view system, group or user node information directly. You investigate any user, group, or system name in the environment by simply typing in the first few characters of the name – the tool will autocomplete. Once you select a node, the “Node Info” field in the left panel populates. You can also right-click a node and choose the sub-option “Expand” to see the members of that node, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3: BloodHound Pre-Built Analytics Queries When looking for hidden administrator accounts and trust misconfigurations, we will commonly use the pre-built queries “Find Top 10 Users with Most Local Admin Rights” and “Map Domain Trusts.” These queries will provide some quick wins and show you which accounts have access to the most systems, and whether there are two-way trusts between foreign domains that could allow for greater access to the environment. Another great way to find hidden administrator accounts is to view system, group or user node information directly. You investigate any user, group, or system name in the environment by simply typing in the first few characters of the name – the tool will autocomplete. Once you select a node, the “Node Info” field in the left panel populates. You can also right-click a node and choose the sub-option “Expand” to see the members of that node, as shown in Figure 4.  Figure 4: BloodHound User Interface Another way we have been able to easily discover hidden administrator accounts is to search for a sensitive system such as a domain controller. This can be done by simply searching for the “Domain Controllers” group and left-clicking the group node. The “Node Info” field on the left will populate. Next, left-click the number next to “Direct Members” under the “Group Members” section. You will now see all the domain controller system nodes under that group, as shown in Figure 5.

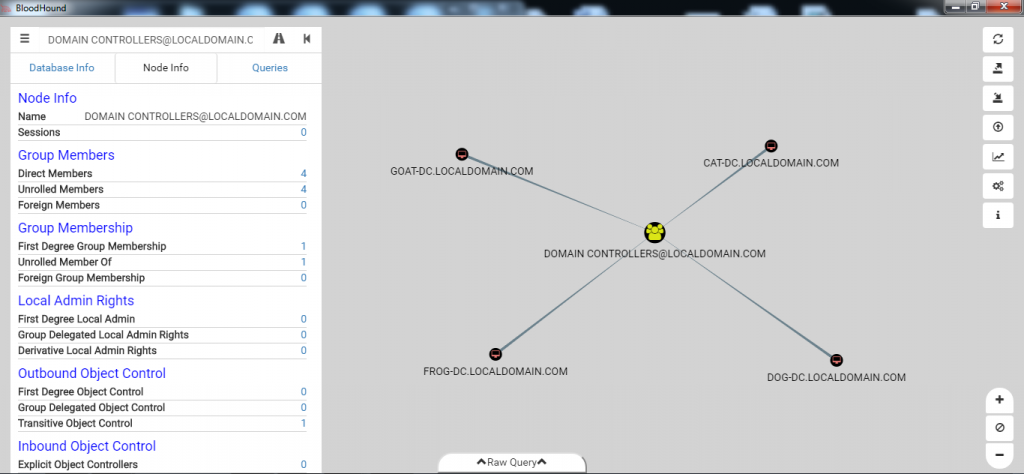

Figure 4: BloodHound User Interface Another way we have been able to easily discover hidden administrator accounts is to search for a sensitive system such as a domain controller. This can be done by simply searching for the “Domain Controllers” group and left-clicking the group node. The “Node Info” field on the left will populate. Next, left-click the number next to “Direct Members” under the “Group Members” section. You will now see all the domain controller system nodes under that group, as shown in Figure 5.  Figure 5: BloodHound Domain Controller Group Members Next, left-click on one of the system nodes (example: “GOAT-DC”) and left-click the number next to “Derivative Local Admins” under the “Local Admins” section, shown in Figure 6.

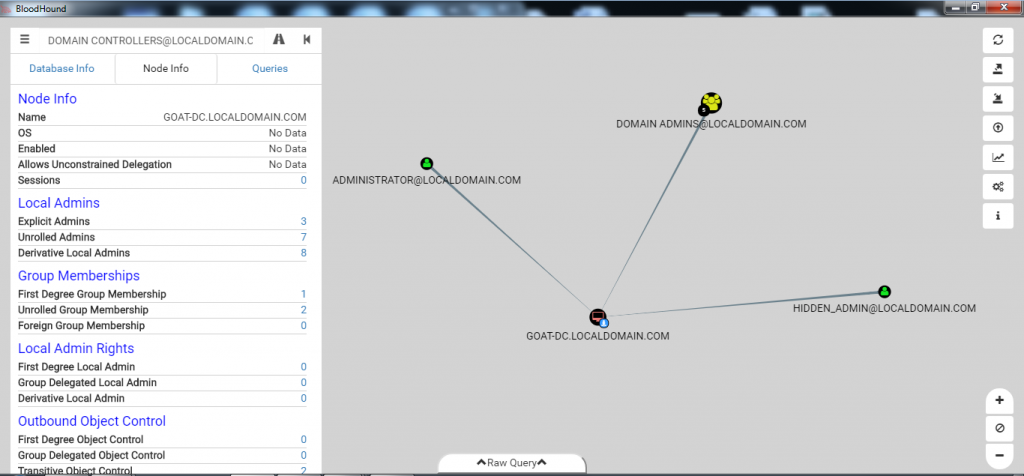

Figure 5: BloodHound Domain Controller Group Members Next, left-click on one of the system nodes (example: “GOAT-DC”) and left-click the number next to “Derivative Local Admins” under the “Local Admins” section, shown in Figure 6.  Figure 6: BloodHound GOAT-DC Derivative Local Admins Now we can see there are two accounts that have local administrator access to our domain controllers that are not in the “Domain Admins” group and did not even show up in Figure 4. We just found two hidden administrator accounts that have similar access to a domain administrator account. It is very likely one of these accounts may be used for automated tasks, which makes them very desirable for an adversary looking to blend into normal environment activity.

Figure 6: BloodHound GOAT-DC Derivative Local Admins Now we can see there are two accounts that have local administrator access to our domain controllers that are not in the “Domain Admins” group and did not even show up in Figure 4. We just found two hidden administrator accounts that have similar access to a domain administrator account. It is very likely one of these accounts may be used for automated tasks, which makes them very desirable for an adversary looking to blend into normal environment activity.

Conclusion

Hidden administrator accounts in an environment are often forgotten, or completely unknown. They can provide attackers with a discreet way to obtain domain administrator rights and fully compromise an environment. BloodHound is highly effective at identifying hidden administrator accounts and is both powerful and easy to use. It can provide a wealth of insight into your AD environment in minutes and is a great tool to have in your arsenal when hunting for unique and hidden relationships. We recommend organizations take advantage of free tools like BloodHound and include them as part of their periodic, proactive security assessments. The more proactive we are in security, the better we can anticipate threats, prepare our teams, and improve our ability to stop breaches. Learn about CrowdStrike Services proactive services offerings. Download the CrowdStrike Red Team data sheet.

![Helping Non-Security Stakeholders Understand ATT&CK in 10 Minutes or Less [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/video-ATTCK2-1)

![Qatar’s Commercial Bank Chooses CrowdStrike Falcon®: A Partnership Based on Trust [VIDEO]](https://assets.crowdstrike.com/is/image/crowdstrikeinc/Edward-Gonam-Qatar-Blog2-1)